Agricultural Expansion

Increasing populations means the further expansion of agriculture. There are 3 main methods:

Ploughing - New modern forms of deep ploughing sites disturbs any archaeological layers close to the surface, and also allows wind and rain to erode the site as the protective layer of topsoil is churned away. Ancient methods of ploughing created relatively shallow furrows, and were unable to reach many sites as they were too high and steep, or the archaeological soils were too dense. This remained the case until tractors became more common in the latter half of the twentieth century. Three instances of agricultural impacts are shown in Figures 1–3.

Figure 1: The site of Tell Farfara (Wilkinson 2000) in Syria (marked in red), as seen on a June 2010 DigitalGlobe satellite image on Google Earth. The lines across the site, and in the fields around it, are plough furrows. At its highest point in the centre, the site is 13 metres high, but is still ploughed, demonstrating the effectiveness of modern machinery.

Figure 2: Proximity of ploughing to sites can compromise their integrity and accelerate site damage due to exposure, as seen in this 2013 aerial photograph of the site of Kefeir Abu Sarbut in Jordan (APAAME_20130414_MND-0315 Kefeir Abu Sarbut 2).

Figure 3: A 2014 aerial photograph of the site of Udhma in Jordan (APAAME_20141012_REB-0095 Udhma). The area around one section of the site is completely ploughed, whilst the other half has been destroyed to plant an orchard.

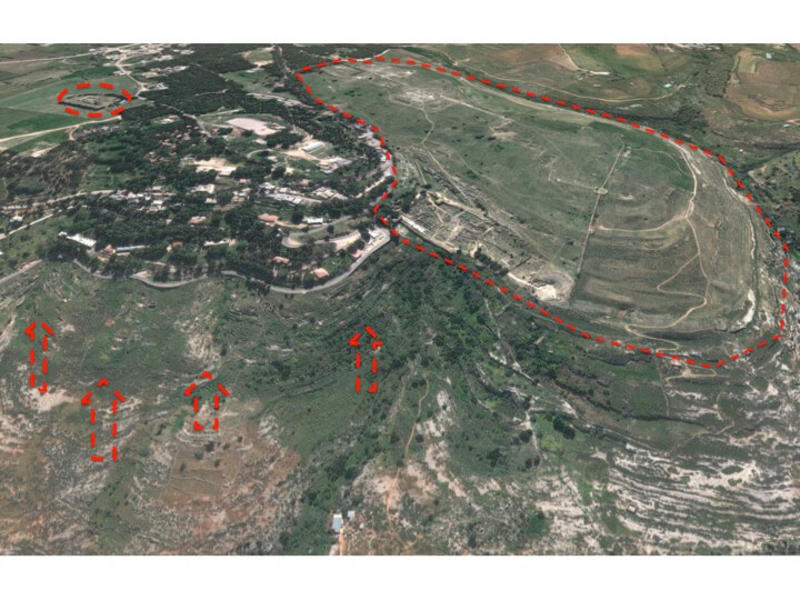

Terracing - The creation of new terraces to expand agricultural land, or for development, is often extremely destructive for archaeological sites as the area is bulldozed flat, removing most, if not all, traces of sites and features. Figure 1 show tombs in the hills around the Greco-Roman World Heritage city of Cyrene in July 2007 (Copyright: Nichole Sheldrick).

Figure 1: Cyrene, Libya, 2007

Unfortunately, as can be seen on a DigitalGlobe satellite image on Google Earth (March 2009, Figure 2), a relatively modern development has been terraced into the hillside above the tombs (marked with red arrows), probably destroying some of the archaeological features of the site (marked in red). The modern settlement predates the World Heritage inscription and the management plan for the site.

Figure 2: Cyrene, Libya, 2009

Orchard Planting - The planting of an orchard can cause damage in two ways. Some orchards are composed of trees planted in individual holes a metre deep, destroying the upper level of the site in that area. Other orchards contain very small trees, but need the area to be cleared. As the trees grow, the roots will interconnect, destroying the rest of the upper levels. This satellite image from June 2010, and a photograph taken just a month later, shows new orchards (marked in blue) planted in the ancient town of Serjilla, one of the World Heritage Ancient Villages of Northern Syria (Figure 1). The Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums, the Syrian antiquities authority, has been working hard to implement protection measures for sites against threats like this.

Figure 1: Serjilla, Syria, 2010

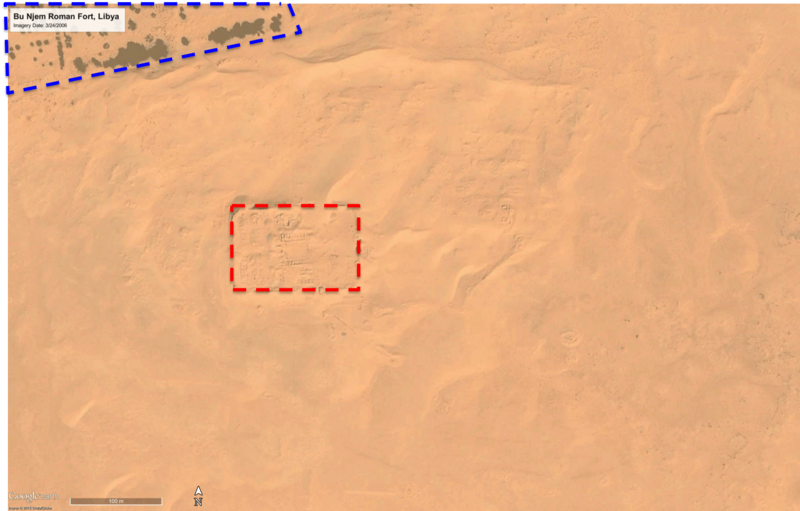

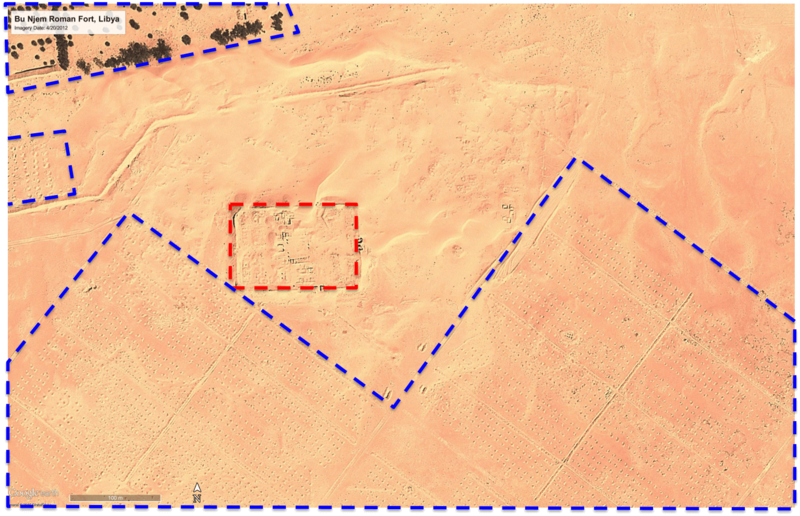

Many orchards are much larger, such as this orchard on Bu Njem Roman Fort, in Libya (Figure 2). The satellite images (DigitalGlobe, viewed in Google Earth) show a well-developed orchard (marked in blue) to the north of the site (marked in red) in March 2006. By 2012, the fort is surrounded by new, industrial-scale orchards (marked in blue). Each spot in the grid to the south and west of the fort is a deep hole, dug for a new tree. Many are overlying or within ancient buildings surrounding the fort. Orchards are extremely damaging and destructive to the upper levels of sites, and, in particular, to archaeological features or sites that sit on the surface.

Whilst removing surface or subsurface features, orchards can, in some cases, also act to protect archaeological sites that have several metres of buried deposits; other forms of land development can cause far greater damage. Although sites with planted orchards may no longer be accessible to archaeologists, they are, at least for a time, protected against irreversible destruction and damage.

Figure 2 (below): Bu Njem Roman Fort, Libya