The Day of Archaeology: 2015

Friday 24 July is the ‘Day of Archaeology’, where archaeologists describe their working day to ‘help show the world why archaeology is vital to protect the past and inform our futures’. And today (Tuesday 21st July) it’s my turn to write a blog post for my Project! So who am I, and what do I do?

Well, the best place to start is an introduction.

Hi! I’m Emma Cunliffe, a fairly newly minted Doctor (2013). My research has always focussed on how to protect sites in the Middle East for damage, whether in peace or during war, so when I was offered a job at the University of Oxford, looking at Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa, I leapt at the chance. The project is recording damage to sites across the region, mostly using satellite imagery and aerial photographs, but with some survey information, and field notes too. We’ve designed a specialist database, which will deal with how complicated that can be (and if it sounds simple, just wait until we put up some of our blog posts!). Once we’ve tested it, which we’re doing right now, we’ll be entering thousands of sites. This will let us analyse damage across the entire region, looking at what the biggest threats are. ISIS feature a lot in the news, but in some areas, threats like agriculture and urban development are even more destructive.

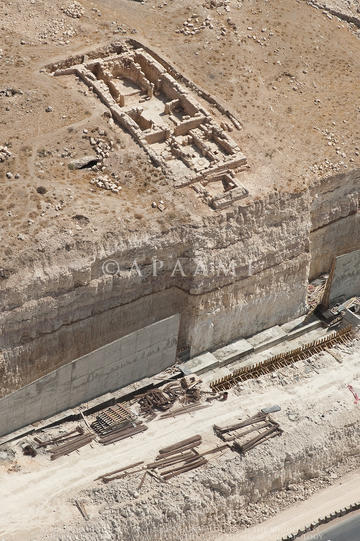

Figure 1: Tall Umeiri (East) APAAME_20101002_SES-0277 ©Stafford Smith, Courtesy of APAAME)

I’ve started my day by scanning for news about site destruction, mostly via Facebook, and then made sure to share this with organisations that might be interested. I’m also part of a team of volunteers that write a newsletter for the NGO Heritage for Peace, for example, listing all the damage that has occurred to sites in Syria. Sometimes, news checking can be quite depressing, but it also gives me hope: Today I found an article about the reconstruction of the shrines in Mali after they were destroyed by extremists. As well as helping us record the damage to the sites, it also informs us what people are doing to protect them, so EAMENA can assist wherever possible.

For example, EAMENA are organising a workshop, ‘Protecting the Past’ in Jordan, and I’m helping a group at Oxford to organise a public workshop to raise awareness of the destruction of heritage in Syria and Iraq (hopefully held in Oxford on 31st October – watch this space!). There’s a bunch of emails about it in my inbox, which is my next task. At the moment, we’re looking for ways to fund travel and accommodation for our speakers. We also want to be able to record the workshop, to make it as accessible as possible, and the V&A has kindly offered to sponsor that, and potentially to provide lunch for those attending, which is wonderful news.

Figure 2: A pendant cairn, on DigitalGlobe imagery on Google Earth.

I myself am speaking on that topic this weekend, at the Ashmolean Museum, as part of the Festival of Archaeology. The subject is ‘What the World is Losing’, and my talk follows Dr Paul Collins, Curator of the Near Eastern Collections, who is speaking about Iraq. Then I’m speaking about site destruction in Syria, and then Dr Robert Bewley, the Project Manager of EAMENA, will speak about our project, the scale of the problem, and how it can help. My talk is called ‘Syria: the World’s Vanishing Past’ (and why is coming up with the title always one of the hardest parts?!) I’ve jotted down some thoughts, but this morning’s job is to write my slides and notes. It’s tough. Hundreds of sites have been damaged in the conflict, by shelling and looting, and even stone robbing and illegal building. It’s not possible to discuss them all, and I’m worried if I focus on just one or two, people won’t realise the extent of the damage. There aren’t even any confirmed counts of how many sites are damaged, although the conservative estimates are bad enough. A lot of people want to know about ISIS, too, to understand more about the religious extremists and their crusade to destroy the idols, but I want to make the point that a lot of sites were damaged in the conflict before they came on the scene; and that ISIS are not even the only people destroying sites for religious reasons. And it’s not just sites that are being damaged – I have evidence of the tragic loss of Syria’s intangible heritage too – silk weaving methods using hand looms, traditional soap recipes, styles of cooking handed down through generations, music that can trace its roots back to the 3rd century AD, 1st century AD church liturgies – all of this is threatened or lost as people flee to refugee camps. An article in this morning’s news talked about one of Syria’s last vineyards. I also want to talk about how hard the Syrians, and the international community, are working to protect their sites. We hear so much about the destruction, but do people in the West know how important their heritage is to the Syrians – so important that some of them have died protecting it? To me this is as important – if not more important – than actually talking about the damage. People will kill for heritage, and they will die for it – it’s not just stones.

I look at all the notes I’ve made: I only have twenty minutes. Perhaps I could talk really, really fast and … No, that’s just being silly. So I decided not to devote any time to talking about ISIS. I know they’ll be covered in the Iraq talk before me (as the damage there is notable), and I expect they’ll come up in the questions, and in Syria at least, we’re not actually sure how much damage they’ve caused yet. For all that Palmyra has been in the news, people can google and easily find the latest news by the Association for the Protection of Syrian Archaeology and the ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative – Palmyra: Heritage Adrift , so I decide to leave that too. I’m just going to give an overview, highlighting how many sites have been damaged, and the types of damage. That should give me time to talk about all the other issues. My rough plan decided, I figure I’ll fill in the last details on the train tomorrow.

Figure 3: A stone walled kite, on DigitalGlobe imagery on Google Earth, probably built to corral animals, hence the enclosures at the ends of the walls, and in the centre of the wall. However, it may also have had a religious function at some point in its use, as there are also a number of cairns associated with it. (Note the modern track to the west and north, threatening the site).

The afternoon is devoted to the bread and butter of the EAMENA Project. I’m scanning Google Earth looking for archaeological sites. My particular area of study (at the moment) is a part of Syria that, before the conflict, was scheduled to be inundated by a major dam project. Whilst this has been put on hold, I’m examining the area to see if there are more sites than were recorded in Syria’s records. As it happens, there are – hundreds – possibly even thousands more. In an uninhabited hilly area, there are a huge number of cairns (stone mounds used for burials or made through field clearance), and lines of walls that may have been used for water management or animal management, many of which could be several thousand years old. I have to admit, I can’t decide which is more exciting – ancient cemeteries or field systems that might be thousands of years old. Of course, some of them may be quite recent – until it’s possible for archaeologists to get into the field, we’ve no way of knowing except through experience of similar sites.

Sadly, some of the sites I’m recording, I only know about as clusters of looting holes, meaning there is a real risk that by the time archaeologists are able to record the site, there may be little left for us to see, and a chunk of Syria’s history will be gone forever. From the patterning of the holes, my guess is that these holes are in an ancient cemetery, and my team agree, but we can’t tell from imagery. The holes cover a large area, though – a site this large has probably been recorded by someone already: I make a note to check in the library for any records. It’s very easy to criticise looters, particularly when I see damage on this scale, but then I remember how difficult the situation is in Syria today. The prices of basic things l take for granted, like food and fuel for heating, have spiralled, and jobs are scarce. Winters reach sub-zero temperatures, and starvation is a real threat – the International Rescue Committee reported that ‘Surveys show the price of bread has risen by up to 500 per cent” by December 2013 – how much worse must it be now?’ That’s not to say all looters are driven by poverty, but it would be too easy to tar them all as profit-driven fanatics.

Figure 4: Small area of looting holes on DigitalGlobe imagery on Google Earth: the concentration of holes suggests that there is an archaeological site there, although we can’t know for certain.

There are some areas in my study area for which Google Earth has no high resolution imagery – I use the ‘Add Polygon’ function of Google Earth to draw round them, and make a note. At the end of the day, I’ve finally finished my grid square, and – whilst I’m more than a little cross-eyed from staring at pixels – my total is good. Overall, I have recorded hundreds of new sites, many of which are well preserved, and even without analysing my data, I have a good idea of the main causes of damage. Properly analysed, this will allow us to develop priorities for protection with the Syrian authorities, and perhaps even new surveys when archaeologists are able to return to the field.

Soon I’m going to see about getting hold of some CORONA satellite imagery. The CORONA series are declassified spy satellite images from the 1960s, showing the landscape before the major changes we see today. They aren’t as high resolution as the highest imagery available on Google Earth (c. 0.5m), but they are pretty good. In some places the resolution is 2m, hopefully good enough to let me look at the areas I’ve noted on Google Earth, and it will even let me look ‘under’ the modern towns and villages that have expanded across the area today! Today has been pretty good – I wonder what I will find next?