The difficulty of verifying heritage damage reports

Dr Michael Fradley writes about the difficulty of verifying heritage damage reports

As part of its aim to record episodes of heritage damage, the EAMENA team responds to reports across the MENA region, often originating via short social media statements. This is far from a simple process, and investigating the fragmentary reports is, in some cases, more complex than the original narratives would suggest.

An example of this is the report of the aerial bombing of a religious site on Jabal an Nabi Shu’ayb, c. 25 km to the south-west of Sana’a in Yemen. This religious complex was referred to by UNESCO as the 9th-century mosque of the Prophet Shu’ayb (also known as the biblical figure Jethro), whose tomb is believed to be located in the vicinity of the mosque. It also has the regional name of the mosque of Bani Matar, adding to confusion when trying to identify it. There are also two rival claims to the location of the shrine of Nabi Shu’ayb; one at Kafr Zeitim in northern Israel, and the other in the Wadi Shu’ayb in the vicinity of al-Salt in Jordan. The mountain itself is the highest in the Arabian Peninsula, with a peak of c. 3,700 masl. A video report and numerous still images on social media dating from 24 August 2016 offered evidence that an incident had occurred, and the case was condemned by UNESCO as an example of unnecessary and indiscriminate aerial bombing of heritage sites by the air forces of the Saudi-led coalition engaged in operations in Yemen.

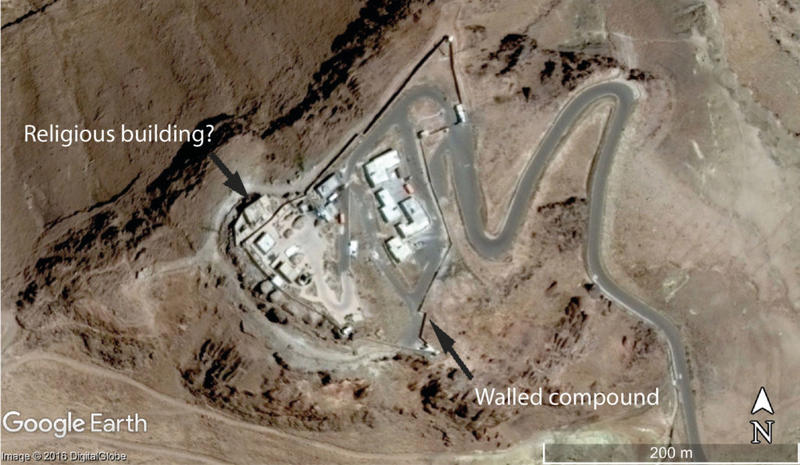

Satellite imagery available through Google Earth shows that this seemingly simple narrative of heritage destruction is more complex. Even the process of identifying the structure in question proved difficult. Available satellite imagery of the summit of Jabal an Nabi Shu’ayb (the publically identified location of the damaged mosque) indicates that a walled compound with mast structures was built there, and there is no visual indication of a structure with architectural embellishments suggestive of a religious function (Fig. 1). A Wikipedia article (accessed 14 October 2014) stated that the mountaintop was used a military base: this is most probably the walled enclosure identified on satellite imagery, with the mast structure suggestive of a communication role.

Use of ground footage as part of the identification process was further hindered as various reports on the incident, including the full video report, were removed from online sources, emphasising the transient nature of online reporting. Other reports appear to have utilised images of entirely different mosque sites (e.g. http://yemenipress.net/archives/52778).

Comparison of the satellite imagery with the reports of the damage to the religious structure enabled the EAMENA team to pinpoint the probable location of the religious building in question. A structure with a distinctive courtyard and a bulldozed trackway can be seen on both this footage (which it is hoped is the correct site as it does show a damaged building) and to the west of the walled compound on satellite imagery. It seems likely, then, that the building in question is to the north side of the walled compound: a plain, unadorned building with little to distinguish it as a religious site other than its location adjoining, but outside, the walled complex. This identification is supported by a comparison with a tourist report of the site, which mentions that a reservoir, visible to the south-west of the identified structure in Fig. 1, was situated next to the mosque and attached tomb, and also discusses the adjacent military compound.

Figure 1. A satellite image of the summit of Jabal an Nabi Shu’ayb captured on the 20 March 2014. The mountaintop is dominated by the walled compound, with the probable religious structure located on the north-west side of the compound (DigitalGlobe via Google Earth).

However, the narrative became more complex when we analysed sequential satellite imagery on Google Earth, which demonstrated that much of this walled complex had already been damaged prior to August 2016. The imagery shows a damage pattern on the buildings and walls of the probable military compound consistent with aerial bombardment, although the external building tentatively identified as the mosque was unharmed (Fig. 2). The damage must have occurred between the available imagery dates of 20 March 2014 and 3 March 2016, and most likely occurred shortly after the escalation of the current conflict in early 2015. At the time of the most recently available satellite imagery from 3 March 2016 there was no visible structural damage to the probable religious building. The imagery in question is high resolution DigitalGlobe and CNES/Astrium RGB imagery with a pan-sharpened resolution of 0.5 metres.

Figure 2. A satellite image of the summit of Jabal an Nabi Shu’ayb captured on the 3 March 2016. Multiple structures in the walled compound have been damaged, but the probable religious structure has not been directly affected (CNES/Astrium via Google Earth).

Limited research into the details of this case has produced a far more complex narrative than suggested by the original reports. The widespread suggestion that this was an indiscriminate attack on a religious building of historical importance is complicated by the knowledge that it was, from an aerial perspective, a non-descript structure attached to a military compound that had already been heavily bombed in the previous twelve months. In spite of the risk that had been clearly demonstrated to the religious site, there is no evidence that its vulnerability had been flagged to the international community following the original bombing of the compound prior to 3 March 2016. The fact that no reports mention the presence of the adjacent military compound, while video footage following the bombing of the site in August 2016 coincidentally only captures perspectives on the site in which the compound is visually absent, would suggest that all reference to the military use of the mountain summit was deliberately omitted.

There was, and still is, a corresponding lack of knowledge about this religious site in the public domain, perhaps in part caused by the apparent military restrictions that forbade access to the summit of the mountain. This report is not intended to provide any justification or reasoning of events that led to the bombardment of this building, but rather is an attempt to make an important point on how we report potential cases of heritage destruction. In this case, the lack of basic checks has revealed a flawed argument behind the highlighting of Jabal an Nabi Shu’ayb as a wilful attack on a Yemeni heritage site. It is also highlights the complexities of understanding these incidents in the context of the 1954 Hague Convention. In this case there is little to suggest that the government of Yemen signalled the cultural significance of the site to the international community, and indeed, the development of the adjacent compound for military purposes may invalidate any legal protection afforded to the religious site.

It is understandable that when reporting about events, particularly using social media, non-essential details are often omitted. However, issues such as the militarised nature of the site have been neglected, which highlights the potential for misinformation and for heritage destruction to become an unwitting part of a politically-motivated campaign. This can only be avoided by clear reporting and fact checking. The broader danger is that in highlighting cases such as the Yemeni example that can be so easily disputed we risk undermining other claims of indiscriminate (and often deliberate) heritage destruction. That is to say, if this case was misreported, how many other examples will turn out to be similarly flawed, and should be disregarded? When we make these claims, particularly where wrongdoing is asserted, then as with any legal claim we must have a strong, evidence-based case to back it up. Ultimately these problems reinforce the need for the work of the EAMENA project to continue and accelerate, drawing together comprehensive heritage datasets that can be searched and cross-referenced when reports of damage emerge.

I am very grateful to my colleagues Dr Emma Cunliffe and Dr Andrea Zerbini for their input to this blog.