The Endangered Archaeological Site of Faida

Posted 10/6/2020

Dr Francesca Simi writes

The archaeological site of Faida is located only few kilometres south of the modern city of Duhok in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The site is an extraordinary rock art complex consisting of a 6.5 km long Assyrian canal and a series of monumental panels sculpted in low-relief along its side. The canal was partially investigated in 2019 by a joint Italian-Kurdish expedition of the University of Udine and the Duhok Directorate of Antiquities co-directed by Daniele Morandi Bonacossi and Hasan Ahmed Qasim.

I took part in the emergency excavation activities carried out by the University of Udine and the Directorate of Antiquities between September and October 2019. These activities were supported by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG – Iraq), the Directorate General of Antiquities of the KRG, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research, the Friuli Venezia Giulia Regional Government, the Friuli Banking Foundation, ArchaeoCrowd Ltd, and the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation.

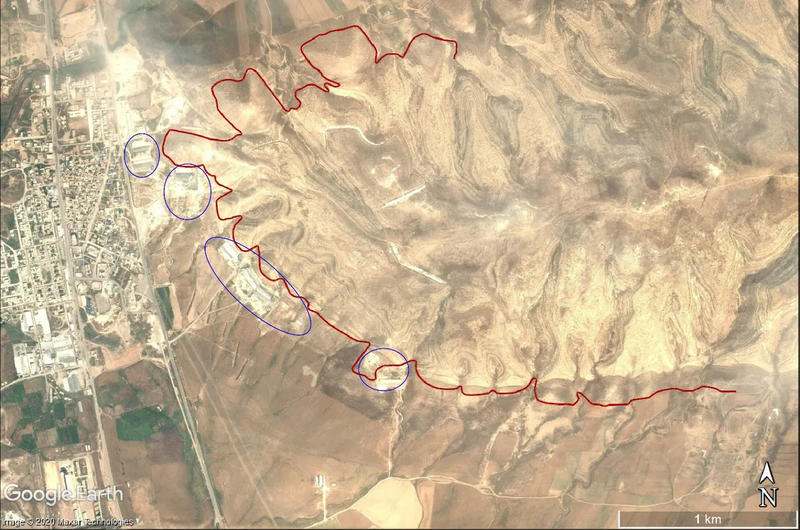

The project started with the intent to rescue the archaeological site that was and still is severely threatened. In the post-conflict phase in this area, the ancient canal and its remarkable rock art are under threat because of various anthropogenic factors, including, vandalism, illegal excavations and the expansion of the nearby village. The damages and threats to the reliefs have increased dramatically in recent years as is clearly visible on Google Earth (GE) satellite images (Figs. 1–2).

The Faida canal, which rounds the western spur of the Çiya Daka hill range, was possibly planned by the Assyrian King Sargon II (721–705 BC) and it is part of a gigantic and highly sophisticated hydraulic engineering network that deeply transformed the landscape of Assyria. Between the end of the 8th and the beginning of the 7th century BC, the Assyrian rulers built in the heartland of the empire (the Governorates of Duhok and Ninawa in modern Iraq) a unique and monumental irrigation system to water the capitals countryside (Khorsabad and Nineveh) and bring water to Sennacherib’s royal palace and gardens on Nineveh’s main upper town (Morandi Bonacossi 2018, Orazi 2019).

The newly engineered waterscapes were associated with commemorative monuments (rock reliefs, rock stelae and royal inscriptions) placed at symbolically charged locations. Faida represents one of the most extraordinary examples of this type of monuments.

The Faida canal has been known since 1972, when the British archaeologist Julian Reade discovered three rock reliefs buried by the filling of the canal (Reade 1973 and 1978). Subsequently, the site was visited by Rainer M. Bohemer in 1978 (Boehmer 1997). During his short visit, he noticed the presence of the reliefs, which he described only briefly. In those years of conflict between the Kurdish Peshmerga and the army of the Baathist regime, the political and military instability that characterized the region meant that excavation of the site was not possible.

In August 2012, during the archaeological survey of the Assyrian canal, the Italian team of the Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project (LoNAP) identified the presence of six new reliefs partly buried by the fill of the canal, thus bringing the total number of known reliefs to nine. Only the upper part of the panels carved in relief emerged from the debris that filled the canal; in some cases, the top of the tiaras worn by the deities could be seen. In spite of this discovery, the necessity of guaranteeing the safety of the reliefs, especially with respect to the advent in the adjacent Mosul region of the Islamic State/Daesh in 2014, led to the suggestion that the archaeological investigation of this unique rock art complex should be postponed until a time when the protection and suitable conservation of these monuments could be ensured. In the years between the birth of the Islamic State/Daesh as a self-proclaimed state entity in 2014 and its defeat in Iraq, the Faida reliefs were located only 25 km from the front line. However, the severe threats that have endangered the archaeological site in the last few years made it necessary to start a joint Italian-Kurdish archaeological salvage project at the site in 2019 to urgently record and protect it.

I have been working in the Governorate of Duhok with the LoNAP team since 2013. In September 2019, I was gladly able to took part in the emergency excavation activities at Faida, where the digging of the canal’s filling brought to light ten unique Assyrian rock reliefs carved on the eastern side of the canal hewn into the limestone bedrock (fig. 3).

It was an extraordinary discovery, since Assyrian rock reliefs are extremely rare monuments. With the sole exception of the single Mila Mergi stela of Tiglath-pileser III, found in the 1940s in the mountains north of Duhok, the last extensive groups of Assyrian reliefs discovered in Iraq were made known to international scholarship almost two centuries ago – in 1845 – by the French Consul in Mosul Simon Rouet, who identified the impressive reliefs in Khinis and Maltai.

The ten panels show the Assyrian King (possibly Sargon II) on both sides of a procession of seven deities mounted on their sacred animals (fig. 4–5). The deities can be identified as Ashur, the main Assyrian god, on a dragon and a horned lion, his wife Mullissu sitting on a decorated throne supported by a lion, the moon god Sin on a horned lion, the god of wisdom Nabu (?) on a dragon, the sun god Shamash on a horse, the weather god Adad on a horned lion and a bull, and Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, on a lion.

The project is at present planning to continue the investigation at the site (other panels could possibly be still buried by the canal filling) and to prepare a protection, preservation and promotion plan of the archaeological complex.

Due to the severe threats endangering the archaeological site, in October 2019, after their excavation and documentation, the reliefs were provisionally protected from weathering and vandalism through the use of non-woven fabric sheets laid on the reliefs and their backfilling with gravel (at the bottom) and earth.

Nevertheless, the backfilling of the Assyrian reliefs is only a temporary solution that cannot guarantee the protection of the archaeological site from the expansion of the factories and farms already besieging the ancient canal (fig. 6).

The archaeological site of Faida, therefore, has yet to be fully explored, studied and understood in its entirety and, above all, it must be urgently rescued from destruction through adequate protection, conservation and management.

The site and relative archaeological and preliminary condition assessments are now in the EAMENA Database (EAMENA-0189699).

More information about the site is available here.

References:

Boehmer, R.M. 1997, Bemerkungen bzw. Ergänzungen zu Ğerwan, Khinis und Faidhi, Baghdader Mitteilungen 28, 245–249 .

Morandi Bonacossi, D. 2018, Water for Nineveh. The Nineveh Irrigation System in the Regional Context of the ‘Assyrian Triangle’: A First Geoarchaeological Assessment, in H. Kühne (ed.), Water for Assyria, Studia Chaburensia 7, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 77–115.

Orazi, R. (ed.) 2019, The Archaeological Environmental Park of Sennacherib’s Irrigation Network. Recording, Conservation and Management of the Cultural Heritage of the Northern Region of Iraqi Kurdistan, Forum, Udine.

Reade J.E. 1973, Excavations in Iraq 1972-73, Iraq 35/2, 203–204.

Reade, J.E. 1978, Studies in Assyrian Geography. II. Notes on the Inner Provinces, Revue d’Assyriologie 72, 159–162.

Figure 1 – Google Earth image of the archaeological site of Faida in 2004 (in red the course of the canal).

Figure 2 – Google Earth image of the site in 2010 (in red the course of the canal and in blue the new farms and factory built a few meters from or directly above the ancient canal).

Figure 3 – The excavated canal with two carved panels side by side (Credits: photo A. Savioli, LoNAP).

Figure 4 – The procession of god statues (Credits: photo A. Savioli, LoNAP).

Figure 5 – A particular of one of the rock reliefs (Credits: photo A. Savioli, LoNAP).

Figure 6 – A drone shot of the canal and the factories besieging it (Credits: photo A. Savioli, LoNAP).