The Ottoman Hajj Forts of Southern Jordan: a tale of damage and preservation

Posted 6/7/2018

Dr John B Winterburn writes

I first visited Jordan in 2006 as the Landscape Archaeologist for the Great Arab Revolt Project (GARP, n.d.). Over nine seasons, this project investigated the archaeology of the Arab Revolt of 1916–1918 and discovered extensive Ottoman militarisation of a landscape built to defend the Hejaz Railway against attacks from the Hashemite Arab Army and British forces (Saunders 2018). Comprising gun emplacements, trench systems, hill-top forts, karakolls, camps and RAF airstrips these features were previously known only to a few Bedouin. My involvement led to a wider interest in the landscapes of Jordan and, in 2015, I successfully completed my PhD researching the ‘Conflict Landscapes of Southern Jordan’.

My landscape survey work frequently brought me into contact with the ancient Hajj route and the Ottoman forts in the remote area to the south of Ma’an. The Syrian Hajj pilgrimage route, known as the Darb al-Hajj al-Shami, is of great antiquity and has its origins in pre-Islamic trade routes dating back at least 2000 years to the Nabatean period and probably much earlier. In Jordan there are nine forts along this route which were built during the rule of the Ottoman Empire, often on earlier foundations. The Ottoman militarisation of the landscape provided protection for Hajj caravans against attacks from Bedouin raiders.

Figure 1. Fassu’ah Fort. Showing the isolated Fassu’ah Fort and the two birkas in for foreground. Image, R.H Bewley, APAAME_20151006_RHB-0108, 2015.

This blog focuses on three of these forts in South Jordan, located at Ma’an, Fassu’ah and Mudawwara. These have been chosen because, each in its own way, illustrate some of the key heritage protection issues of reconstruction and reuse together with abandonment, looting and destruction.

Figure 2. The location of the forts. Country border data, US Dept of State Geographer. Image, Landsat/ Copernicus and Google Earth 2018.

These forts were visited on numerous occasions in 2009, 2011 and 2014 during field work in the area. Forts at Mudawwara and Fassu’ah were photographed and are now being used to produce records in the EAMENA database.

The forts lie on the Hajj route and a succession of pilgrims and travellers have visited and written about them or the earlier buildings. These included the Moroccan Scholar, Ibn Battuta, in the 14th century AD, the German explorer Burkhardt, British explorer, Charles Doughty in the 19th century, and the Czech anthropologist, Alois Musil, in the early 20th century.

The completion of the Hejaz Railway, from Damascus to Medina, as far as Ma’an in 1904 and Mudawwara by 1905 opened the area to more travellers and a new highway built in the last decades of the 20th century, further enhanced access to the remote forts at Mudawwara and Fassu’ah.

Ma’an

There has been a settlement at Ma’an since pre-Islamic times (Kennedy 2004:184), with the evidence of early Islamic and Byzantine structures indicating that it was a nodal point on the early Hajj caravans. Among the many European travellers in the 19th century was Charles Doughty who travelled with a Hajj caravan. He found stone tools in a nearby wadi when he visited in 1875, indicating prehistoric activity in the area.

Figure 3. Ma'an Fort, 2002. Image D. Kennedy, APAAME_20020930_DLK-0115

Ma’an’s Hajj fort was probably constructed between 1559 and 1563 (Petersen 2012:109) and was located to the south of the original settlement and the Hajj camps. With the arrival of the railway in 1904, the increasing importance of Ma’an and its subsequent expansion, new development surrounded the fort. It continued to function as a government building and was being used as a prison in 1983 (Petersen 2012: 110). Later it was refurbished and then became the regional office of the Department of Antiquities. Today, it sits within landscaped gardens, and has had several recent architectural additions. Despite this, it is probably one of the best-preserved Hajj forts in Jordan.

Fassu’ah

Figure 4. Fassu’ah Fort, east elevation. Image, J B Winterburn, 2009.

Fassu’ah Fort is located 50 km to the southeast of Ma’an on the edge of Wadi al-Msas and is surrounded by the flint, chert and limestone Jebel Sherra plateau. It is 2 km to the west of the relict Aqabat Hejazia railway station and its modern replacement; immediately to the south are the remains of an extensive, modern, gravel quarry.

Figure 5. The internal structure of Fassu’ah Fort. Image, J B Winterburn, 2009.

Although the currently visible fort dates to the mid eighteenth century, it is probable that the site has a longer history, as travellers and pilgrims from the 10th to the 18th centuries made various references to ‘a site among the flints of the Jebel Sherra’. The strategic importance of Fassu’ah is very clear. It protects the head of the descent off the high plateau of the Jebel Sherra and through the notorious pass at Batn al-Ghoul down into the sandy desert in Wadi Rutm. This pass into the ‘Belly of the Beast’ was described by Doughty as a ‘strangling place’ and a ‘sink of desolation’ (Doughty 1888: 23).

Mudawwara

Mudawwara is the most southerly Ottoman and Modern settlement in Jordan. For centuries it has been a caravanserai on the Hajj route and was first mentioned in the 9th century (Petersen 2012:122). Today it is a frontier post and village close to the border with Saudi Arabia.

Figure 6. Mudawwara Fort. Image J B Winterburn, 2010.

The fort and cisterns date to the 18th century and were built on the orders of the Governor of Damascus. It was linked to Damascus by telegraph in 1901, but was effectively by-passed when the railway was built 3 km to the east. The British Army found the fort unoccupied on 7 August, 1918, and used what they mistakenly thought was a Roman Temple as a first-aid post for the attack on the Ottoman troops defending the nearby hill-tops and station complex. Later in the 20th century the fort was re-used by the Trans-Jordanian Frontier force and the Arab Legion.

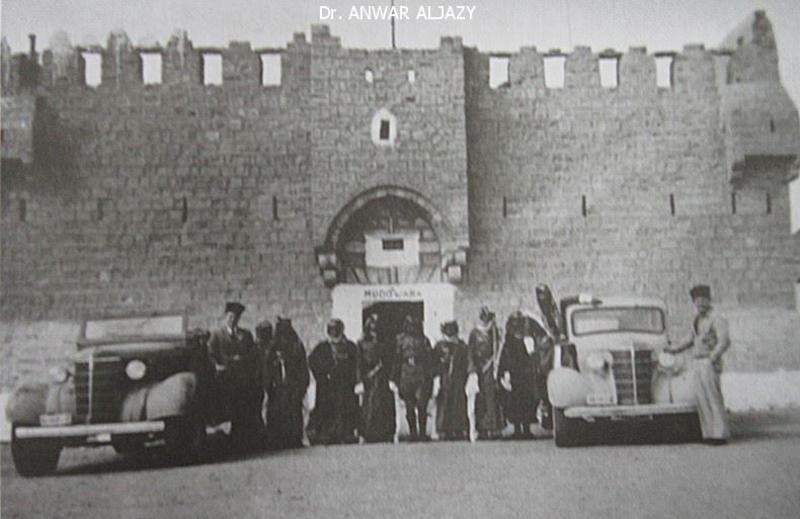

Figure 7. Mudawwara Fort in the mid-twentieth century. Image courtesy of Dr Anwar Aljazy.

Today, the fort is in a state of imminent collapse. The southern elevation has been undermined, probably with mechanical excavators and the entire southern wall has subsided. This has allowed access to the interior of the building and most of the internal features have been removed. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the fort was first bulldozed in the 1980s in the common misbelief that Ottoman gold was buried under the walls. Photographic evidence from 2002 (Khammash 2002) and 2010 (see Figure 8) indicates that much of collapsed masonry from the internal structures and south elevation was removed from the site and that additional damage occurred to the east elevation.

Figure 8. Mudawwara Fort, the collapsed south elevation. Image, J B Winterburn, 2010.

Final thoughts

These three Hajj forts are all under threat but from various agencies, depending on their location. The fort at Ma’an is on the outer limits of a large modern city and probably has more visitors than the other forts to the south. However, it is close to the centre of administration for the region and has been found alternative uses in the recent past. The Ma’an fort has a purpose and function that has extended in to 21st century. Although its present status is uncertain its utility has acted as a powerful agent in its preservation. Its location close to the regional centre of Ottoman and later Jordanian administrations has contributed to its preservation and protection from damage.

Fassu’ah, by contrast, stands in isolation 2 km to the west of a modern industrial rail transhipment facility at Aqabat Hejazia. The fort is in an isolated position, so harder to protect from looting and vandalism and the proximity of industrial facilities provides access to machinery that can be used for unauthorised excavation. The fort has had no real purpose since the early 20th century when its birkas were used to provide water to the nearby Hejaz Railway; a function that ceased in 1918. The fort has also been used as a ‘fire-base’ in joint military exercises with troops from the British and Royal Jordanian armies.

Fassu’ah had a function as a Hajj fort until the railway effectively put an end to the Hajj caravans that would have passed the fort. Its location, in a remote area, hidden from sight at the bottom of a wadi coupled with its proximity to an industrial facility, on a refurbished section of the Hejaz Railway, has made it vulnerable to damage and looting.

Mudawwara Fort is in a remote location, away from the modern village that has developed close to the relict railway and modern highway. It continued to have a function into the 20th century as a regional security post. However, although remote, there is both a sizeable settled and transient population in the vicinity. Looting for building material for the expanding village and the longstanding problem of looking for Ottoman gold have both had a negative impact on the fabric of the building.

Sadly, neither Fassu’ah nor Mudawwara fort receive any statutory protection under the Jordanian Antiquities Law as they post-date 1700 CE. Their future is uncertain, but we will continue to monitor them, documenting any changes or threats to the structures, in the hope that these important structures can one day be better protected.

References

Doughty, C. M. (1888) Arabia Deserta, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

GARP (n.d.) Great Arab Revolt Project, consulted 6/6/2018, <http://www.jordan1914-18archaeology.org>

Kennedy, D. (2004) The Roman Army in Jordan, London: Council for British Research in the Levant.

Khammash, A. (2002) Hajj Hotels, consulted 6/6/2018, <http://www.khammash.com/research/hajj-hotels>

Petersen, A. (2012) The Medieval and Ottoman Hajj Route in Jordan. An Archaeological and Historical Study. Oxford; Oxbow Books.

Saunders, N.J. (2018) Desert Insurgency: Archaeology, T.E. Lawrence and the Arab Revolt. Oxford; Oxford University Press.