Reflections on the EAMENA aerial photograph appeal

Posted 1/5/2020

Dr Michael Fradley writes

Back in early 2017 we started trying to develop access to historic aerial photographs for the MENA region to support the work of the EAMENA project. This work was primarily driven by the need to access high-resolution imagery for The Occupied Palestinian Territories, where U.S. legislation known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment limited the resolution of contemporary commercial satellite imagery for this area. It also built on the earlier work of Professor David Kennedy’s work on our sister project, APAAME, in gathering these historic aerial photographs and our colleague Rebecca Repper’s work in digitising the Sir Aurel Stein and O.G.S. Crawford collections at the British Academy and UCL respectively.

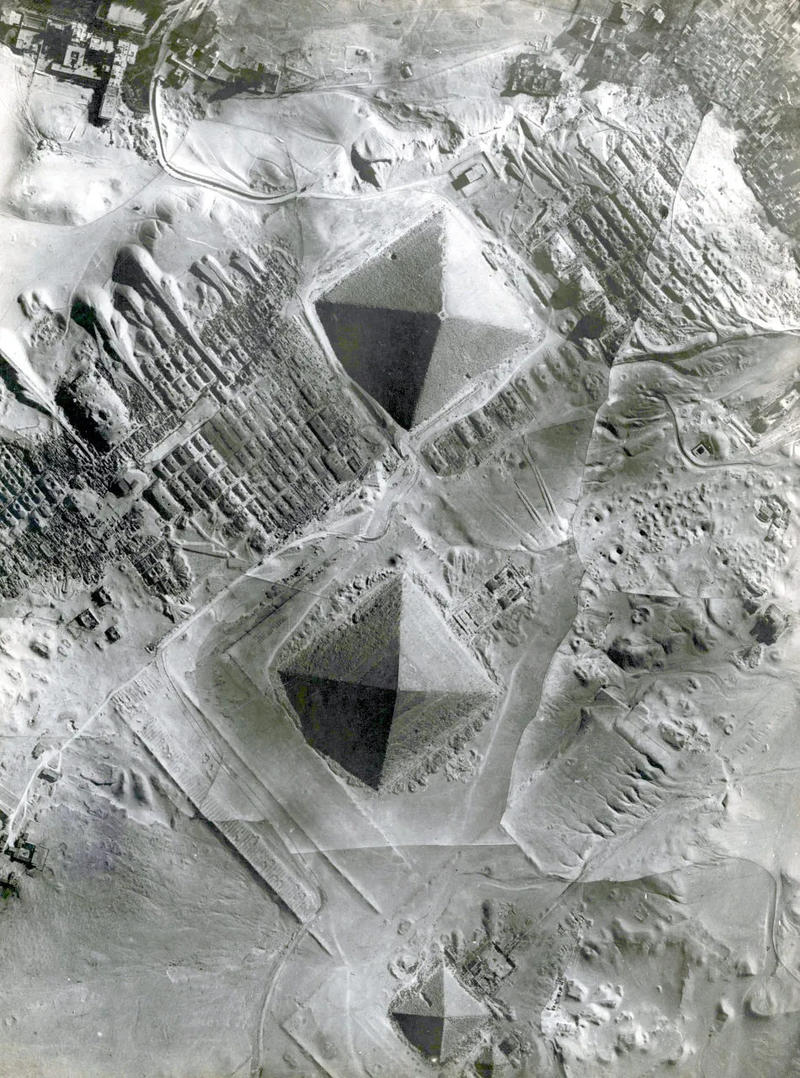

At first we focused on known archives such as the National Collection of Aerial Photography (NCAP) in Edinburgh, and more limited collections at The National Archives in Kew and a range of smaller museums around the UK. However, it was clear that accessing and digitising of these established collections would be resource heavy, while documentary evidence examined at The National Archives suggested that a lot of early, pre-Second World War aerial photography had been archived, at least for a time. For their collections, Crawford and Stein both seem to have drawn on photographs from material in the Air Ministry archives, as well as from squadron bases in the Middle East and North Africa. It seems, however, that many of these collections have not survived in official collections, so we launched a campaign to reach out to the public to see whether any material had ended up in personal collections, particularly via RAF personnel who may have brought back photographs from periods serving abroad (Fig.1).

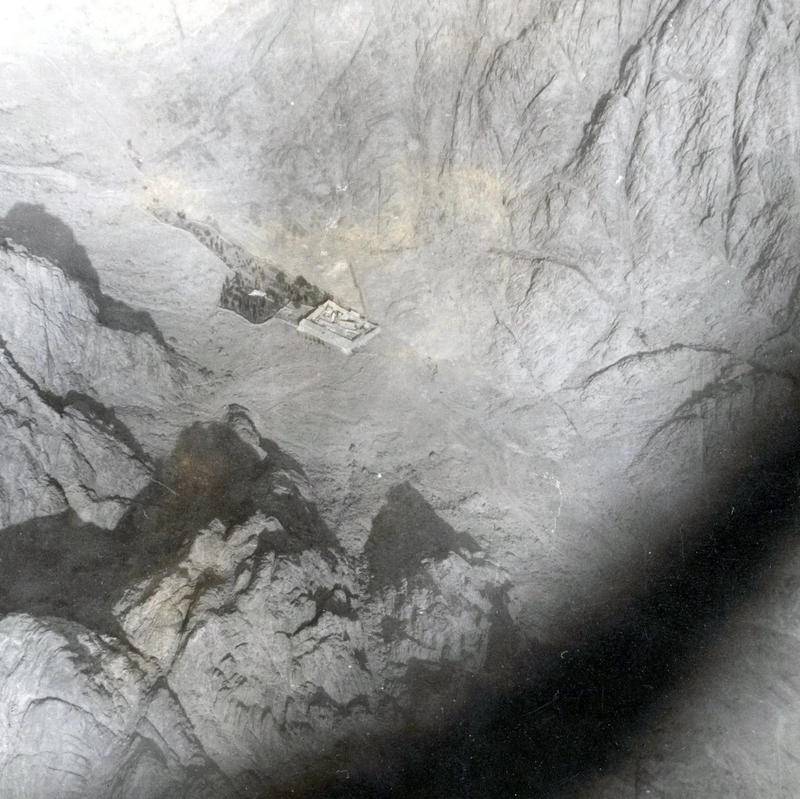

Launching our campaign online, and through veteran associations such as the Royal Air Force Association (RAFA), our work brought in some surprising results and stories. In many cases we heard from the descendants of former RAF personnel, who had inherited photograph collections and generously offered access to their collections and to share them with the EAMENA project. In one case we heard from an RAF navigator who had served in Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen in the early 1950s and was part of a mapping squadron. After very kindly offering his personal photographs that he had taken over Egypt and Jordan, including a fantastic shot of St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai region (Fig.2), he mentioned that he had also worked on missions in what was then the Aden Protectorate (now Yemen), but believed that all the photographs had been destroyed in an accidental fire in Aden. Nearly 70 years later, we were able to tell him that the photographs had, in fact, survived, and that we had been able to create digital copies of them from a collection of prints that are held by the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Going beyond simply investigating aerial photographs taken of known archaeological sites, we have also pursued the technical history of the early use of aerial photographs for photogrammetric topographical mapping (using the same principles as the drone-based photogrammetric modelling that has become popular in archaeological survey in the last decade). Many experimental missions were undertaken during the inter-war period across the Middle East and North Africa, where there was a general lack of medium- and large-scale mapping available. We have been lucky enough to gain access to a number of these early aerial mapping missions, and will be publishing research on the development of British photogrammetric mapping in the MENA region in the near future.

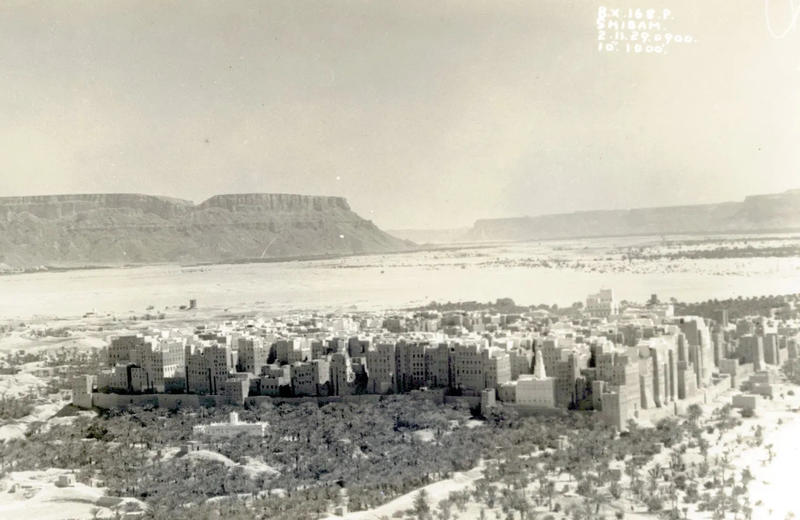

We were also able to track down relatives of some of the individuals involved in this pioneering mapping work, such as John Salt, who held the role of Research Officer for the UK’s Air Survey Committee in the early 1930s. Thanks to the generosity of his family in sharing his collections, we were able to make digital copies of a series of oblique aerial photographs from Yemen, which he picked up while on a short triangulation mission to Aden (Fig.3).

Frustratingly, our research into these historic mapping missions has also given us glimpses into projects for which we have not been able to trace any surviving photography. One of the earliest of these was a relatively experimental map to be built using aerial photographs of the Yenbo/Rabeg area on the western coast of what is now Saudi Arabia, undertaken by ‘C’ Flight of 14 Squadron RFC/RAF, and drawn up as a 1:500,000 map by Captain Thomas Henderson on 20 August 1917, with multiple copies surviving. This operation was undertaken by the British forces, including T. E. Lawrence, in support of the Arab Revolt. Although copies of the map survive, none of the original mapping photographs could be tracked down of what may have been the first aerial mapping mission in Arabia. These squadrons working in this region would go on to undertake aerial mapping missions across Palestine, Jordan, Syria and Iraq.

Of even greater archaeological value is a series of aerial mapping missions taken along the course of the Nile in Egypt, from Aswan to the Cairo Barrage that were undertaken in 1920, 1921, and 1922. These missions involved Stewart Newcombe, who had been involved in the Arab Revolt operations in 1917, and were initiated to better plan for flood preparation across the region. Archaeologically, they would be of exceptional value, providing an opportunity to re-assess a dense archaeological landscape that has been transformed by settlement expansion and agricultural intensification over the last century. Although Newcombe published an example photograph from the 1920 flight (Newcombe 1921), we have not been able to find any of these collections, and it is possible that they have not survived. We were contacted by a member of the family of Flight Lieutenant P. J. Barnett MC (Later Wg Cdr) who flew as part of the 1920 mission while based at Helwan. Although his family did not have any surviving copies of the aerial photographs, F. L. Barnett’s log book indicated that 1,200 photograph plates were taken during the 1920 mission in September of that year at an altitude of 14,000 feet, and that across the three years, these missions would have potentially produced over 3,000 photographs. It is not impossible that at least part of this collection may still survive in an unexplored archive or in private collections. The resulting maps may have been produced by the Survey of Egypt, and could potentially have been inherited by a later Egyptian mapping agency such as the General Survey Authority (ESA). We can only hope that at least some of these photographs will come to light one day, and can be used for the benefit of research in archaeology and other geographical-related sciences.

Outside of the RAF, commercial companies such as the Aircraft Operating Company (AOC) would also undertake photographic surveys in the MENA region. An irrigation survey of the Tigris River in Iraq was organised in the late 1920s and undertaken by the company, although as with the Nile example above, the whereabouts of any surviving photographs is currently unknown.

Our aerial photograph appeal has been a great success, and we are incredibly grateful to all those who have provided the EAMENA project with access to their photographs or taken the time to support our work. We would still be interested to hear about any further historic aerial photo collections that have not yet been on our radar, or any further information about these collections. The next step is for us to improve access to these collections through the EAMENA database, to allow researchers outside of EAMENA to use and explore these important pieces of the historical record. We have already managed this for collections over Egypt and Jordan, and we will report on further developments on this front. In the meantime, make sure to check out the collections already available on the APAAME Flickr site.

Newcombe, S. F. 1921. ‘Contouring by the stereoscope on air photos’. The Royal Engineers Journal 34, 49–55.

Fig.1. A 1930s vertical photograph over the pyramid complex at Giza, Egypt, generously shared with the project by Owen Masters.

Fig.2. A 1951 oblique view of St Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, Egypt generously shared to the project by John Clubb, formerly a member of 683 Squadron RAF.

Fig.3. An oblique view of Shibam in Yemen taken on 2 November 1929 by a member of 8 Squadron RAF, generously shared the project by the Salt family. Fig,3. An oblique view of Shibam in Yemen taken on 2 November 1929 by a member of 8 Squadron RAF, generously shared the project by the Salt family.