The View from Above: Aerial Photography and Archaeology in Egypt

Posted 5/11/2020

Dr Mohamed Kenawi writes

From balloons in the 18th century, and especially since the invention of photography in the 19th century, the ability to look down from above has been a wonderful discovery opportunity for antiquarians and archaeologists. Aerial photography allows the observer to see, record and interpret archaeological sites that might otherwise never be recorded.

Aerial archaeology in Egypt has been limited to partial trials, which yielded good results in some cases and disappointing results in others. In the 20th century, attempts to photograph major archaeological sites and the landscape in Aswan, Luxor, and Cairo were undertaken using several different methods. In addition, aerial photographs taken by the Royal Air Force, Dutch Air Force, and others during the First and Second World Wars captured archaeological sites, among other targets. These were just the first of many efforts to acquire more photographs from different parts of Egypt. In recent years, different collections have been made available online (Figures 1–3).¹

In Upper Egypt, some attempts to photograph specific archaeological sites in Athribis, Luxor, and in the Fayoum at Qasr Qaroun (Dionysias) and Soknopaiou Nesos, resulted in great photographs due to the contrast between the sandy soil and the structures, which were mainly built out of limestone (Figures 4–6). However, despite the high number of archaeological missions working in Egypt, aerial documentation has remained limited.

Fig. 1: Giza Pyramids in 1930s

Fig. 2. Philie Island, Isis temple, Aswan (EAMENA archive “R.E. Collis collection, courtesy of Joan Allen”)

Fig. 3: Edfou temple, (EAMENA archive “R.E. Collis collection, courtesy of Joan Allen”)

Fig. 4: Qasr Qaroun (L. Passalacqua, Il tempio di Qasr Qarun – Dionysias: tecniche edilizie, architettura e ricostruzione. 2015, fig 32, p. 47).

Fig. 5: Dime, Fayoum, the Hellenistic dromos leading to the temple area (courtesy of Soknopaiou Nesos Project, University of Salento, Italy, photo by B. Bazzani)

Fig. 6: Dime, Fayoum, the temple area and houses in 2014 (courtesy of Soknopaiou Nesos Project, University of Salento, Italy, photo by B. Bazzani)

In the Delta, experimenting with aerial imagery has been limited to four archaeological sites. Attempts were undertaken at Tanis and Kellia. Currently, there are only a few missions working in the Delta, on a small scale compared to those operating in Upper Egypt, with most missions employing traditional methods of documentation (e.g. restricted to ground surveys). The dearth of classical archaeologists working in the region and the difficulty of defining mudbrick structures in muddy, black, silty soil have limited the application of aerial photography. Prior to 2014, the surveys at Tell el Debb’a and Tell Timai attempted to document archaeological features using aerial photography but these were limited to the excavation trenches (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Tell Timai in the eastern Delta, southern area. Courtesy of the Tell Timai Archaeological Project.

An important step in aerial documentation was undertaken at Kom Wasit in 2014 and Kom ed-Dahab by Menzaleh Lake in 2015 prior to ground investigations, revealing previously unknown features of the sites and aspects of the urban layout. At Kom ed-Dahab, a combination of kite aerial pictures and Google Earth images identified new structures such as the remains of a Roman theatre, a temple, a palace, and other structures. No further excavations were conducted on the site until now (Figure 8).²

Figure 8: Kom ed-Dahab, Roman theatre captured by Kite. Marourad, G. From Space to Ground, Aerial Images and Geomagentic Survey at Kom ed-Dahab (Menzaleh Lake, Egyptian Eastern Delta, fig 3, p. 20; courtesy of Tell Timai Archaeological Project, University of Hawaii, USA, Thanks to Jay Silverstein).

Aerial photographs are of great value for archaeologists to identify archaeological sites in the landscape as well as archaeological features within sites. At Kom al-Ahmer and especially at the nearby site of Kom Wasit, it was not possible to detect the remains of any archaeological structures by field-walking during a normal survey day. However, in 2014, aerial photographs were taken at 11am, and the results were surprising: they revealed a number of structures that were not visible from the ground, but appeared in the view from above. However, while these first results were good, they were still not providing a very clear view of the sites and their structures (Figure 9). Thus, more photographs were taken at dawn, just before, and during sunrise, revealing the remains of a complete town. The results of these photographs were very valuable and clearly revealed the layout of a Hellenistic town (Figure 10).

Fig. 9: Kom Wasit, remains of the ancient town (courtesy of Italian mission in Beheira) at 11am

Fig. 10: Kom Wasit, remains of the ancient town (courtesy of Italian mission in Beheira) at dawn.

The contrast between the soil and the mudbrick structures is due to the different rates of humidity absorption and release, and are therefore only visible in the early hours of the day.

This level of contrast is, however, not visible in compact soils such as that of Kom al-Ahmer where most of the ground has been flattened by pedestrians and cars.

Although drones have been banned in Egypt since 2015, it is possible to use kites, balloons, and many other similar methods to produce aerial views. Great images can even be captured with a high-quality camera attached to a very long metal pole (Figures 11–12).

Figs. 11, 12: Using a 12m long metal pole to record archaeological features (courtesy of Italian mission in Beheira)

There is an increasing number of free online platforms and applications providing base maps and tools for identifying sites and structures within sites. The release of 1960s Corona satellite images was essential to understanding the level of damage and even disappearance of some archaeological sites in the Delta over time due to the increase in population and resulting development projects in the region. These images can also be used as a benchmark for the study of archaeological sites in the Delta.³

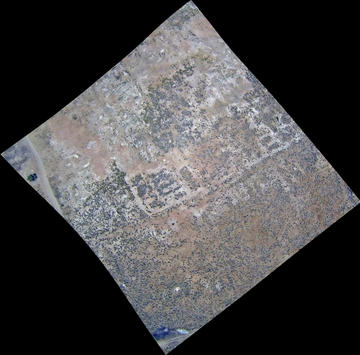

Google Earth imagery has increased in quality, and can be used to monitor changes to sites and landscapes since 2003. More recently, Google Earth Engine has provided the opportunity to monitor changes from 1984 onwards using low-resolution satellite imagery. Finally, programs and applications such as Collect Earth can be used to provide different maps of any specific region (Figures 13–14). The EAMENA project is undertaking a large-scale survey of North Africa and the Middle East using satellite imagery in order to rapidly document the majority of possible identifiable sites.

Figs 13 (left) and 14 (right): Eastern Delta site in 1960s (Corona) and in 2014 (Google Earth)

In the Aswan area, Dr Louise Rayne (formerly an EAMENA team member), in collaboration with Dr Maria Carmela Gatto, are analysing satellite imagery to help inform and understand the field survey results of the AKAP project (Aswan Kom Ombo Archaeological Project), directed by Dr Maria Carmela Gatto. The AKAP field survey is recording sites of all types and all periods. The EAMENA project has also been undertaking condition assessments using the EAMENA methodologies and validation of remote sensing techniques, including the application of applied change detection algorithms to satellite images for this area around Aswan to rapidly identify changes in the landscape around archaeological sites.

As always, in archaeological investigation we should never rely on just one source of information or evidence. Therefore, the combination of satellite imagery, historical aerial photography and new approaches to aerial photography, such as those mentioned above and others such as the use of drones, allows for better and more detailed documentation of existing archaeological sites and aids in the discovery of new ones.

Fig. 15. Aerial view of Athribis, Shikh Hammad, Sohag during the temple excavations, (courtesy of Athribis Project, Marcus Müller)

¹ https://ncap.org.uk/search?page=11&keywords=egypt&view=grid&daterange=&archive=0&camera= (last accessed August 2020); https://www.flickr.com/photos/apaame/albums/72157685540281436 (last accessed August 2020); https://jcarlcalvin.wixsite.com/wwii-photos-maps (last accessed August 2020); https://eamena.arch.ox.ac.uk/category/aerial-photographs/ (last accessed August 2020); https://www.loc.gov/search/?fa=location:cairo%7Clocation:egypt&sp=12 (last accessed August 2020); https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2170/en/ (last accessed August 2020).

² Marourad, G. From Space to Ground, Aerial Images and Geomagentic Survey at Kom ed-Dahab (Menzaleh Lake, Egyptian Eastern Delta), OI.UCHICAGO.EDU/AUTUMN 2016, PP. 17-21).

³ https://corona.cast.uark.edu/atlas#zoom=9¢er=3572803,3604985 (last accessed August 2020).