The Tahoun project: recording endangered Ottoman heritage in Jabal Moussa, Lebanon

Posted 06/06/2019

Letty ten Harkel, Marianne Boqvist, Stephen McPhillips, Owen Murray, and Louise Rayne write:

The Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA) project is pleased to work in collaboration with the Association for the Protection of Jabal Moussa (APJM), Cultural Heritage without Borders (CHwB) and Owen Murray on the Tahoun project, led by Stephen McPhillips and Marianne Boqvist (CHwB Sweden), documenting endangered productive landscapes of the Ottoman period in the Jabal Moussa UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in Lebanon.

The Jabal Moussa UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, covering an area of some 6500 hectares, is located in the Kesrouan District, on the shoulders of the western slopes of Mount Lebanon. It has a rich natural and cultural heritage, with many plant species that are endemic to Lebanon or even Jabal Moussa, as well as being the habitat for nationally endangered animals like the tabsoun or rock hyrax. The reserve also contains many sites of archaeological interest spanning the Bronze Age to Ottoman periods, some of which have been already conserved or restored by APJM (Figure 1).

Other heritage sites, especially those on the boundaries of the reserve – including water mills, various houses and evidence for industrial activities, and a bridge – all are still endangered, hence the need for the Tahoun project (tahoun is the Arabic word for watermill). It focuses on the productive landscapes of the Ottoman (1517/18–1918 CE) period, generally speaking an under-explored period in Lebanese archaeology (Bradbury et al. 2017).

It builds on a previous survey – the Jabal Moussa survey – carried out in collaboration with the EAMENA project and the APJM, which documented the archaeology of the wider landscape. The landscapes of the area have undergone many changes in recent years and the later, Ottoman heritage is especially severely endangered. Uncontrolled quarrying is a major visible threat to the natural and cultural landscapes in the area (Figures 2–4), as are agricultural and construction activities (Figures 3–4).

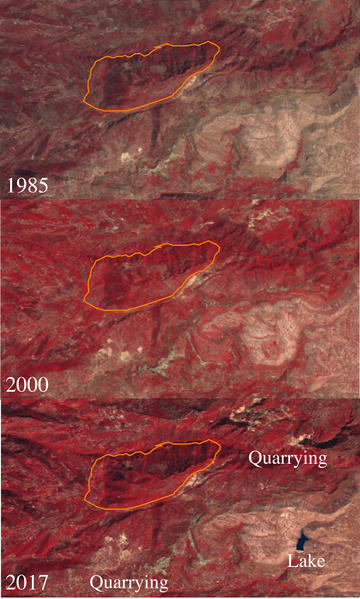

Remote sensing techniques can add further insight into the changes that have taken place, and provide time depth. Dr Louise Rayne of the EAMENA team has recently developed some scripts for Google Earth Engine that allow us to monitor land changes from freely available satellite imagery (including Sentinel 2 and Landsat) from the mid-1980s until the present day. The resolution of these free satellite images is generally not good enough for site identification, but it is very useful to map changes in wider land use. In what follows, a preliminary analysis of imagery from Landsat satellites will be used to highlight certain aspects of the wider landscape change. Landsat satellite imagery since the 1980s can provide the greatest time depth from the available free imagery.

Comparison of cloud-filtered composite Landsat satellite imagery from the mid-1980s (01-01-1985 to 01-01-1986), 2000 (01-01-2000 to 01-01-2001) and 2017 (01-01-2017 to 01-01-2018) shows the aforementioned quarrying activities encroaching on the southern and northern edges of the reserve, as well as road building or widening (Figure 5). These activities seem to have intensified more recently, after the 2000 composite image. More detailed analysis of imagery at shorter time intervals can shed more light on the timescale of these activities. The rapid destruction of the natural landscape surrounding the reserve underlines the importance of the work undertaken by the Association for the Protection of Jabal Moussa.

Interestingly, the Landsat imagery also shows an overall increase in vegetation since the 1980s. The vegetation increase in the wider area is at least partially a result of changes in agricultural practices, such as a decrease in grazing on the mountains. This, of course, also has allowed the flora within the reserve to grow to its current exceptional richness that has resulted in its special status as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, but at the same time it represents a threat to the surviving heritage (Figure 6).

Tree roots grow between the dry-built walls and disturb their integrity. Many building stones are cracking, and the walls are collapsing. Other natural conditions also impact on the surviving architecture: in the winter, the area can be covered in snow and in the summer exposed to hot temperatures.

From a remote sensing perspective, it is also worth pointing out that vegetation increase renders it gradually more difficult to see much of the archaeology from the air, reinforcing the importance of combining remote sensing and ground survey for a full understanding of any given region’s archaeology and heritage.

The EAMENA project– in collaboration with colleagues from CHwB – is now contributing to safeguarding the unique character of the reserve through this project that aims to integrate the surviving Ottoman heritage into the reserve’s management plan. CHwB are commenting on the structural integrity of the buildings and providing specialist advice on their potential reconstruction or structural consolidation, whilst the EAMENA team is supporting the protection of the structures and contributing to a detailed digital documentation of a select number of them. Their protection is important, as they provide a uniquely well-preserved relic of the Ottoman rural past, showing an integrated land exploitation strategy combining agricultural and industrial practices (Figure 7).

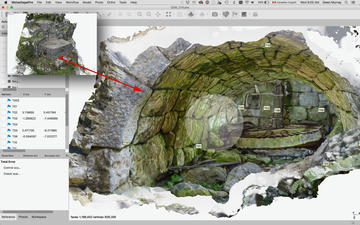

The digital documentation process is carried out in collaboration with photogrammetry specialist Owen Murray, who is producing detailed 3D models of several of the surviving structures (Figures 8–9). These include a limekiln and two houses inside the reserve, as well as a well-preserved water mill and a bridge in the wider region.

The photogrammetry element was carried out in a rapid documentation context, moving between structures at 1–3 day intervals. Where access allowed, they were modelled inside and out to obtain a detailed understanding of their functioning. Models were geo-referenced using the waypoint averaging function of two handheld GPS devices taking multiple samples (where possible on consecutive days).

Prior to the photogrammetry, the Association for the Protection of Jabal Moussa undertook a controlled clearance process to free the buildings from vegetation (Figure 10). Taking place within a biosphere reserve, this emphasised the need to find a delicate balance between cultural and natural heritage, which is already at the foreground of the reserve’s awareness and policies. The relationship between vegetation and heritage sites is worth considering for a moment. Vegetation cover can protect heritage structures to a degree – for example from human disturbance factors facilitated through easy access – but also can have a damaging effect as tree roots deform walls or foundations. A balanced management approach that values the flora and fauna of the reserve on an equal footing with the heritage will now be developed.

The fieldwork was completed in May 2019 and the next steps involve the creation of a best practice manual and on-line teaching materials in the form of short 10-minute lectures, as well as a three-day, on-site training course in August to transfer knowledge and raise awareness of the importance of the Jabal Moussa Biosphere Reserve. An interpretative article on the Ottoman productive landscape will furthermore be submitted to Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises.

The EAMENA project is looking forward to continue working with the Association for the Protection of Jabal Moussa and is grateful to the Swedish Institute Creative Force programme for funding the project and to the Arcadia Fund for covering salary costs for EAMENA staff.

References

Association for the Protection of Jabal Moussa

Bradbury, J., Flohr, P. and Ten Harkel, L. 2017. Lebanon’s Heritage at Risk: part 3.

Cultural Heritage without Borders

Landsat-5, -7 and -8 images courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, obtained via Google Earth Engine.

Figure 1: Tahoun project members walking past a partially restored rural farm building of the Ottoman period along one of the walking trails through the reserve in May 2019.

Figure 2: Ground photo of quarrying along the road leading towards one of the entrances to the Jabal Moussa Reserve.

Figure 3: Photo taken from the southern slopes of Jabal Moussa, showing the impact of quarrying, a road and agriculture (facilitated through the easy access provided by the road) on the landscape surrounding the reserve.

Figure 4: Photo taken during a drive along the southern edge of the reserve, showing the impact of quarrying and construction on the landscape.

Figure 5: Three composite Landsat satellite images from 01-01-1985 to 01-01-1986 (L5, bands 4, 3 and 2), 01-01-2000 to 01-01-2001 (L7, bands 4, 3 and 2) and 01-01-2017 to 01-01-2018 (L8, bands 5, 4 and 3), generated using Google Earth Engine (script by Louise Rayne). The red colour indicates vegetation. The pale blotches, especially in the southern and north-eastern areas, indicate quarrying. The lake is visible in the latest imagery in the bottom right quadrant. The approximate outline of the reserve is sh

Figure 6: Ottoman farmhouse, partially overgrown by wild vegetation.

Figure 7: Interior of endangered Ottoman mill documented by the project, showing remarkably well-preserved in situ wheel.

Figure 8: 3D model (textured mesh, Agisoft Metashape) of interior of the same endangered Ottoman mill.

Figure 9: Photogrammetry specialist Owen Murray in action on the Ottoman limekiln.

Figure 10: The same building as in Figure 6, after vegetation removal. Note the agricultural terraces and greenhouses in the background, as well as the newly constructed houses. In the back corner, photogrammetry specialist Owen Murray is taking measurements to improve the accuracy of the model.