EAMENA Iconem Exhibition

Understanding Archaeology through Remote Sensing: Mapping 3D Archaeology

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region contains hundreds of thousands of important archaeological sites, from prehistory to past classical civilisations and more recent cultural heritage. With so many sites at risk of damage it would not be possible to visit them all. Using remote sensing we can rapidly understand, document, and visualise the cultural heritage of the Middle East and North Africa, contributing to its protection.

Publicly available satellite imagery – Google Earth, Bing, and Apple maps especially – is crucial for rapid documentation. The results can be enhanced by the examination of vertical and oblique aerial photos, as well as more detailed drone and ground imagery. Laser scanning and Lidar imagery can reveal more detail, as well as reveal what is under vegetation; while underwater photography and seabed mapping provide essential detail on submerged sites and landscapes.

The five case studies below in this exhibition: Um al-Jimal, Taq Kasra, Yazidi Cultural Heritage, Cyrene and Apollonia all demonstrate that each of these approaches is viable in their own right. Their potential is vastly increased when they are used together, illustrating the crucial contribution of new technologies to the understanding and documentation of archaeological sites.

Umm al-Jimal

Rising out of Jordan’s northern basalt plain, beautiful Umm al-Jimal (Arabic: ام الجمال, "Mother of Camels"), is a village in Northern Jordan approximately 17 kilometres east of Mafraq. Umm al-Jimal is both a modern town and an ancient archaeological site, home to almost 2000 years of fascinating history and culture - Nabataean, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Mamluk, Ottoman and Modern.

Although it is primarily notable for the substantial ruins of a Byzantine and early Islamic town, which are clearly visible above the ground, as well as an older Roman village (locally referred to as al-Herri) located to the southwest of the Byzantine ruins, what makes Umm al-Jimal stand out in this landscape is not just its larger size, but its remarkable state of preservation. Whereas neighbouring settlements are badly ruined and quarried out, at Umm al-Jimal one can still see the the standing remains that composed this ancient success story. Not only that, but Umm al-Jimal has served successive generations from its first century origins up to its resettlement in the 20th century by Syrian Druze and bedouin Msa'eid people. In fact, its last inhabitants are still living older members of the modern community, many of whom can say, “Yes, we lived in this house and drank the water from that reservoir,” pointing to an ancient house and its nearby birkeh. The heritage of Umm al-Jimal as a settlement has therefore been enduring, and has been a major formative influence on the cultural identity of modern Jordan.

An ancient water reservoir at Umm al Jimal (Bijan Rouhani) |

A pathway in Umm al-Jimal (Bijan Rouhani) |

Taq Kasra (Ctesiphon)

Tāq Kasrā is the remains of a Sasanian-era Persian monument, dated to c. the 3rd to 6th-century, which is sometimes called the Arch of Ctesiphon. It is located near the modern town of Salman Pak, Iraq. It is the only visible remaining structure of the ancient city of Ctesiphon, Seleucia and Veh Ardashir, a dense urban area spanning both sides of the Tigris River. The wealth of the area was derived from its agriculturally productive hinterland – Mesopotamia - the bread basket of the Sasanian Empire. The archway is considered a landmark in the history of architecture, and is the largest single-span vault of unreinforced brickwork in the world.

As part of the EAMENA-CPF (Cultural Protection Fund) training in endangered archaeology, employees of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage assessed the condition of the site in March 2019. Documentation of its condition through satellite imagery, historical photographs, and continued monitoring by on-site condition assessments are crucial to preserving this spectacular site for future generations.

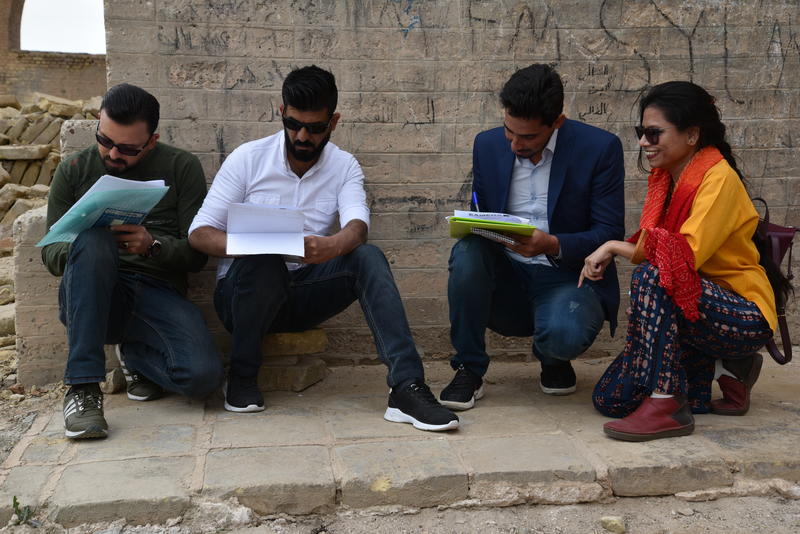

SBAH & EAMENA assess condition of site, March 2019 (EAMENA) |

Site with the North Wing visible, reconstructed in the 1970s. (EAMENA) |

Yazidi Cultural Heritage

The Yazidi people trace their identity and faith back over 6000 years to ancient Mesopotamia. The Yazidi community is concentrated in Northern Iraq where the holiest site of the Yazidi faith, Lalish, is located.

In the summer of 2014, Islamic State (IS) began a series of assaults on the Yazidi (Êzidî) community in northern Iraq. The intention of IS was to eradicate the Yazidi people and their beliefs through ethnic cleansing and genocide. One facet of this was the destruction of Yazidi cultural heritage. Lalish became a place of refuge for many Yazidis fleeing from advance of Islamic State in the greater region.

Together with RASHID and Yazda, the EAMENA project participated in the production of an open-access report entitled Destroying the Soul of the Yazidis: Cultural Heritage Destruction During the Islamic State’s Genocide Against the Yazidis. The report presents the results of an investigation into cultural heritage destruction that occurred during the genocide. To learn more about the genocide committed against the Yazidi people, you can also visit Nobody’s Listening. There you will find information about the virtual reality experience and immersive exhibition commemorating the genocide and telling the stories of the survivors, which is launching in 2021.

Amadin Temple-Sinjar (Yazda-Faris Mishko) |

Sheikh Mand Temple (Yazda-Faris Mishko) |

Cyrene

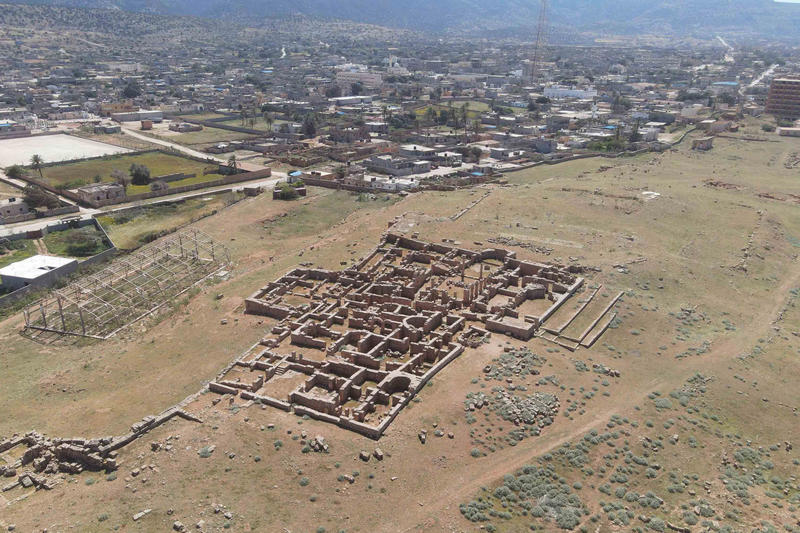

Cyrene was an important Classical city of ancient north-east Libya. Originally founded by Greek settlers in the 7th century BC and continuing as the pre-eminent city of the region through the Roman period, the ancient site of Cyrene is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. However, there are many parts of the site outside this area which are under threat of damage and disturbance. The rapid expansion of the modern city of Shahat immediately south-east of Cyrene is a main cause of this damage.

A well-known feature of Cyrene is its north necropolis, featuring hundreds of tombs covering the north slopes of the site, dating from the 6th c. BC until the 5th c. AD. Urban expansion and road widening is encroaching on these tombs. Issues such as graffiti and looting are also a problem here.

North Necropolis, general view, facing East (Nichole Sheldrick) |

A tomb with graffiti (Mohamed Kenawi/Manar al-Athar) |

Apollonia

Apollonia was founded as the port town of inland Cyrene in the 7th century BC probably because its sheltering reefs offer one of the few safe anchorages on the rugged Eastern Libyan coast. Archaeological remains include numerous Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine structures onshore and extensive harbour elements on the outlying islands and also submerged on the seabed (a consequence of tectonic activity). Despite being one of North Africa’s best-preserved ancient harbours, it is threatened by coastal erosion and urbanization. Coastal erosion is eating away at the site, exposing unrecorded material and putting buildings at risk from collapse. Although this is a long-term process, it seems to be accelerating and will speed up as the surrounding protective reefs break down and are overtopped by a combination of climate change-induced sea-level rise and enhanced storm activity. Over the last 20 years, the modern town of Susah has expanded considerably and, in some places, encroaches directly on the protective fence surrounding ancient Apollonia’s core. Outside the fence, archaeological features like cemeteries and extramural buildings are at risk from unregulated construction. Some, like part of the western necropolis, have already been lost. This online exhibition showcases these threats and demonstrates the approaches we can use to document and quantify their impacts.

East shoreline of Apollonia, where effects of erosion are visible (Saad Buyadem) |

Drone footage of Apollonia (©Fouad El Gumati) |

This exhibition has been produced as part of a training and capacity building scheme, funded by the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund (CPF).

The EAMENA and MarEA projects have been supported by Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, and the British Council’s CPF.