EAMENA Volunteering – Assessing the Condition of Samarra, an Endangered World Heritage Site in Iraq

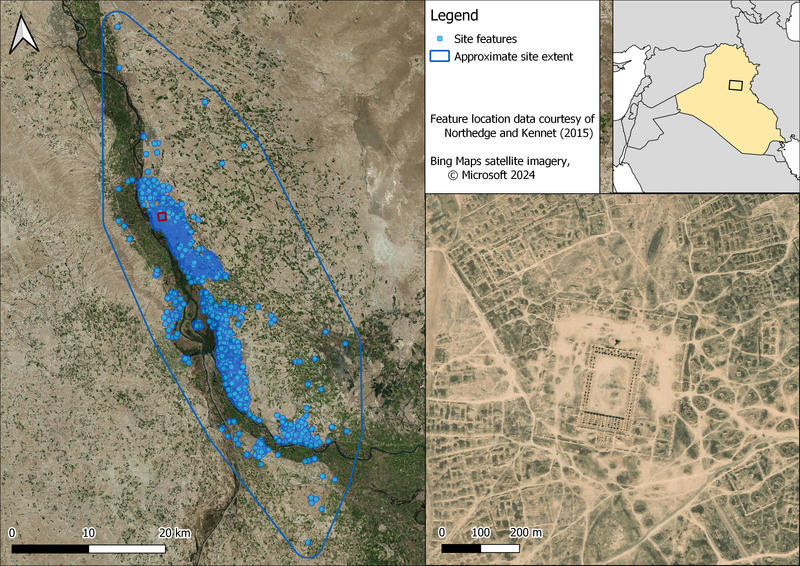

Whilst studying archaeology as an undergraduate at Durham University, I became involved with the EAMENA project as a volunteer. The Early Islamic city of Samarra in Iraq (Figure 1) is under severe threat by agricultural and urban development. I worked as part of a volunteer team of undergraduate and postgraduate students carrying out condition assessments on thousands of site features originally recorded in the Archaeological Atlas of Samarra (Northedge and Kennet 2015).

Figure 1 – location, scale and approximate extent of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Samarra, Iraq.

Samarra

Samarra was a short-lived capital of the Abbasid Caliphate – often known as the Golden Age of Islam – which at that time covered a huge area stretching from modern-day Tunisia to Yemen, Iran and Syria. Founded in 836 AD by Caliph al-Mu'tasim, Samarra showcased Abbasid wealth and power. The city covers an area of approximately 150 square kilometres, encompassing grand palaces and mosques, and thousands of other structures. Samarra was abandoned in 892 AD, after less than 60 years, when Baghdad was reinstated as the Abbasid capital, leaving behind an unique Early Islamic city of global archaeological significance. The site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007.

After lying almost untouched for over a thousand years, conflict in recent decades has resulted in Samarra coming under significant threat from military use, modern agricultural and urban development. It has been on the UNESCO ‘List of World Heritage in Danger’ since its inscription. Two decades later, as no systematic remote-sensing condition assessment had been carried out to document damage to the archaeology at Samarra, the EAMENA project chose to undertake such a study as part of a volunteering project at Durham University. High-resolution satellite imagery and historic aerial photography (Figure 2), the latter as originally used to document the archaeology of the site in the later 1980s (Northedge and Kennet 2015), were deployed to assess the current state of Samarra.

Figure 2 – comparison between historic aerial photography from 1953 and recent high-resolution satellite imagery of a central part of Samarra ,© Google Earth 2024.

EAMENA Volunteer Condition Assessment

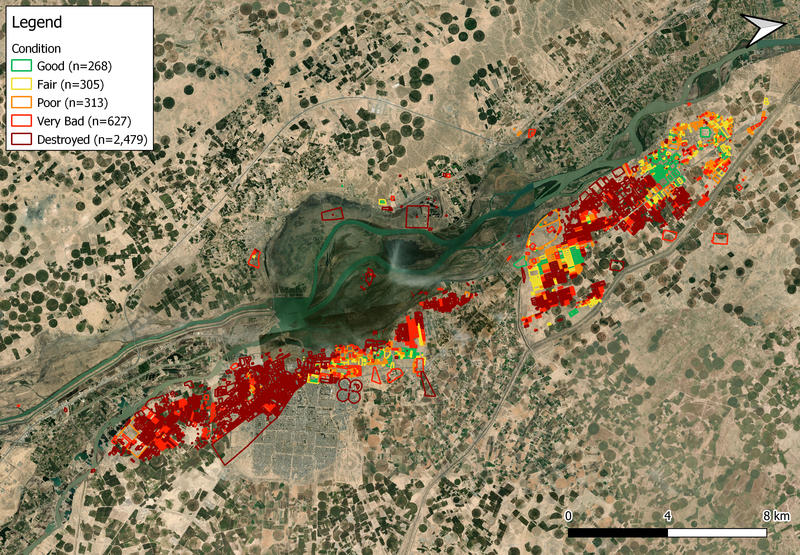

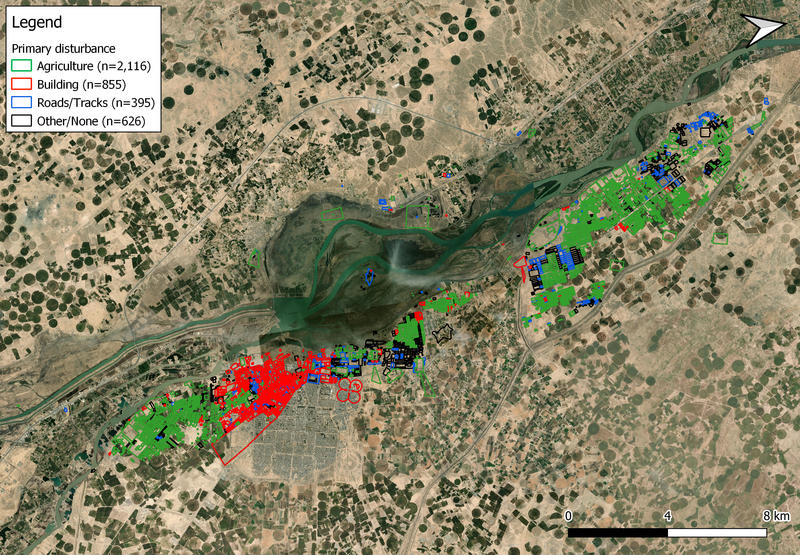

A team of fifteen Durham undergraduate and postgraduate student volunteers carried out weekly two-hour sessions over two terms to assess the state of the site. Working with the feature polygons originally drawn for the Atlas, and using the 1950s aerial photography as a guide, approximately 4,000 individual features were identified and assessed. The overall condition of each was recorded on a scale from ‘Good’ to ‘Destroyed’, and any visible damage was recorded using an optimised version of the EAMENA system. ‘Damage extent’, the approximate area of disturbance, was also recorded.

We have now assessed around 70% of Samarra’s features and are now able to describe some of the large-scale a patterns that are emerging from the data. Based on our remote sensing condition assessment, more than half of the structures have been destroyed (Figure 3). Features in a ‘Good’ condition make up less than 7% of the total, rising to only 14% in a ‘Good’ or ‘Fair’ state. Agriculture is the biggest threat to the site – it makes up the primary cause of damage in over half of all the features assessed (Figure 4). Building and road infrastructure are also major threats to the site. Erosion and natural vegetation are also damaging the archaeology, albeit at a much smaller scale.

Figure 3 – overall condition of features assessed so far at Samarra. Bing Maps satellite imagery © Microsoft 2024.

Figure 4 – primary disturbance(s) for features assessed so far at Samarra. Bing Maps satellite imagery © Microsoft 2024.

There are clear spatial patterns to site preservation and damage. Features in good condition tend to be near the most conspicuous features, the large mosques and palaces. In contrast, many large blocks of ordinary houses have suffered significant damage. Not surprisingly, the features most at risk of destruction or damage through modern building work are those situated close to existing settlements, particularly to the modern town of Samarra. Agricultural damage is unsurprisingly most common in the spaces between urban areas.

This condition assessment work will continue as the new university term begins, with new volunteers joining the team to help establish the current state of this unique Islamic site. We will share all our results with our collaborators in the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage in Iraq, to help with future protection initiatives and to ground truth our remote sensing results.

References

Northedge, A. and Kennet, D. 2015. Archaeological Atlas of Samarra. London: The British Institute for the Study of Iraq. Freely available at https://www.bisi.ac.uk/publication/archaeological-atlas-of-samarra-samarra-studies-ii/.