The Future of UK Archaeology

Posted 26/10/2016

or the less exciting – the Neighbourhood Planning and Infrastructure Bill: local, national, and international perspectives

by Emma Cunliffe, Jon Welsh and Suzanna Joy

This article was published in the recent edition of the Association for Roman Archaeology magazine, and is reprinted here with their kind permission. The ARA is dedicated to supporting and fostering an interest in Roman Archaeology, and to informing its members about it. To find out more about them and their work, and to join, see their website here. Although a UK focused article, it offers an EAMENA perspective on how changes to UK planning legislation could be implemented.

No, you read that right. And if you’re wondering what on earth that’s doing in your lovely issue of ARA News, it’s okay. We have a point, we promise. Read on – this is important stuff, and your opinion matters.

Under pressure to build new housing, the Government announced the forthcoming Neighbourhood Planning and Infrastructure Bill in May, containing proposals to support the delivery of one million homes and deliver necessary infrastructure. The Bill included measures to reform and speed up the planning process by minimizing delays caused by pre-commencement planning conditions; and streamlined processes supporting neighbourhoods to come together to agree plans that will decide where things get built.

Why should we care, we hear you say? Well, there’s cause for lovers of archaeology to be concerned. The UK has a great set- up compared to most countries: planning laws state sites must be evaluated in order to assess the impact the development will have on potential archaeology, and the developer pays for the excavation of any archaeology they find. Sure, it leads to the occasional developer trying to hide his finds to save himself time and money, but in general it’s a great system.

‘Streamlining’ the process is causing alarm. A pre-commencement planning condition is the part of the process that says (in essence): the proposed site has to be assessed to see if it’s likely to contain archaeology; before construction the developer has to take appropriate measures to identify any archaeology on the construction site; and if they find archaeology they have to deal with it appropriately. The Government believes ‘excessive pre-commencement planning conditions can slow down or stop the construction of homes after they have been given planning permission’,1 and that these conditions are overused. The new Bill will ensure they are ‘only imposed by local planning authorities where they are absolutely necessary’.2

Under the new process, local authorities can propose (rather than set) conditions on new development if they are absolutely necessary, and the developer can still challenge them to enable construction can go ahead without delay. The idea is that, once the proposed conditions are set, the developer can then decide if they want to go ahead, knowing what they are signing up for, reducing unforeseen costs and delays (potentially like finding all that pesky archaeology!) Responding to heritage lovers’ concerns, the Government highlights ‘the National Planning Policy Framework remains unchanged in that it requires “developers to record and advance understanding of the significance of any heritage assets to be lost (wholly or in part) in a manner proportionate to their importance and the impact, and to make this evidence (and any archive generated) publicly accessible”‘.3 So it’s okay, right? No one would use vague legislation to cut corners to win the ‘we built houses’ vote… would they?

Having met with Government to voice their concerns over the Bill the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (CIfA), Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers: England (ALGAO) and the Council for British Archaeology (CBA) released a joint statement on the Bill. The statement explained that although officials had stressed to them that archaeology was not a target for reform, the Bill was only one aspect of a wider agenda “which is having a clear negative effect on the protection of archaeology through the planning system”. In conclusion, the archaeology organisations stated that there was diminishing trust in the Government to not harm the historic and natural environment and that “the planning system is no longer working in the interests of archaeology”.

A petition has been launched online to “Stop Destruction Of British Archaeology. Neighbourhood and Infrastructure Bill” because of concerns that “the current Requirements [sic] that force developers to carry out archaeological and wildlife surveys before starting housing projects are to be abolished in the new Neighbourhood Planning and Infrastructure Bill. This will destroy archaeological sites and risk the industry that conducts surveys, excavation and preservation of our vital past.” As of 26 July 2016 it had 18,256 signatures. Under the rules for this type of petition, 10,000 signatures obliged the Government to reply (available online with the petition).

At 100,000 signatures the petition has to be considered for debate in Parliament. Should you sign? Is the petition useful? Is all just scaremongering, and worry over nothing? What could these plans mean in reality? Is the Government right in its response to Jonathan Lester’s petition:4 “This interpretation does not accurately represent the Government’s intention“?

Here we now offer you three perspectives – one from a north-east commercial archaeology company, one from a major national and international development firm (with an excellent recording for managing heritage during development), and an international perspective, from places where development doesn’t have to care about archaeology.

A local commercial archaeology perspective

Jon Welsh, AAG Archaeology

As an archaeology company director I believe the new Bill is only going to make a difficult job more difficult. I regularly deal with developers who are hell-bent on not paying for planning condition archaeology: 75–80% of our invoices are not paid on time; developers frequently try to ignore Government legislation (part of UK law) designed to protect small businesses such as archaeology companies from late payment; and it is not unusual for us to have three or four small claims cases to recover our fees active at one time. We live on a small island with some of the best archaeology in the world, representing every period of human activity, so much of which has already been destroyed since the Industrial Revolution. Only this week I have found Roman archaeology 270mm below the raised patio in the back garden of an ex-council house (Fig. 1). Archaeology is a hallmark of the advanced society living sustainably, not a hang-over from a bygone age of antiquarian pursuits. To ignore it is to risk a future living in ‘the white room’, a characterless, featureless location with no culture or identity beyond the latest business park.

Dealing with developers is especially difficult in the current climate of austerity, which may become worse with Brexit, where local government archaeologists and planning officials are scared of complaints from developers. Paid little and treated with contempt by the construction industry they deal with daily, field archaeologists seem to have diminished self-worth and feel that many members of the public resent their Council Tax going towards a County Archaeology service, responsible for deciding which work gets done, and managing the county’s heritage assets. Yet there is also a feeling that the same people are the first to complain when something on their doorstep, or that they feel has some relevance, is threatened. Dig a trench in the street and people can’t resist their curiosity to find out everything about what is down it, and tell you all the stories about what is meant to be buried nearby. On a larger scale, the same Government that introduced a planning system that no longer properly supports archaeology was faced in the same month with the realisation that £465bn of infrastructure projects over the next eighteen years are at risk of delay due to a lack of archaeologists.5

As members of the ARA you appreciate the importance of proper archaeological investigation to recover artefacts, identify archaeological features and record our heritage before it is destroyed. But there are also economic benefits to archaeology. Put simply – archaeology means jobs: directly, archaeology jobs for people who may otherwise not have jobs, and indirectly for the significant amount of money that archaeology brings into local economies. I see this every day, in the look of relief on people’s faces when I walk into a quiet pub or small rural shop with my field crew. Some years ago, I remember the owner of a local sandwich shop beside a large excavation who asked how long it would be before the dig started up again every single time post-excavation staff went into the shop. Tragically, he got into such financial difficulties during the off-season that he committed suicide by walking into the North Sea.

On a positive note, the Bill does reference creating more apprenticeships, something that must be given serious consideration. Graduates do not figure large in my workforce, most of whom entered archaeology in the 1990s through training-for-work schemes and do not hold degrees. New graduates tend not to last long in the field: university to building site is a culture shock, their shortcomings quickly become apparent, and their expectations are soon dashed. Most have been taught field skills by academics who cannot always dig well themselves as they spend only a token amount of time in the field. Can we really expect future archaeologists to run up massive debts studying for degrees that may have little relevance to the job they will eventually do, the skills for which could be easily learned in the workplace?

At 100,000 signatures the petition will be considered for debate in Parliament. I think it is worth signing at the very least to raise a debate about the reality and future of British archaeology. Archaeologists shouldn’t feel as unwelcome in Parliament as they do on a building site. The All Party Parliamentary Archaeology Group has not updated its website since 2010, although it appears to still be sporadically active, as Lord Renfrew mentioned their work during the Second Reading of the Cultural Property (Armed Conflicts) Bill 2016–17 in June. Why has APPAG been silent on the Bill?

A national development perspective

Suzanna Joy, Arup

Post 23 June 2016, with Brexit looming over us, the question has to be asked, what are the Government’s priorities? Discussions held with a number of planners in-house think that this Bill may be dropped in favour of more pressing issues regarding Britain’s decision to leave the EU. However the concerns surrounding the Bill still raise questions around the relationship between the heritage industry and developers.

The Government’s view is worrying to heritage specialists: by cutting so-called ‘red-tape’, we may lose the necessary processes that protect heritage assets. Also, it is unclear what constitutes ‘excessive’ pre-commencement conditions, and where the balance of proportionality, as defined under the National Policy Planning Framework (NPPF), sits between environmental management and the need for housing. While the Department for Communities and Local Government has tried to reassure the heritage community that archaeology is not a target of the reforms, concerns remain over a number of items. The major concern is that the idea of granting ‘permission in principle’ will enable more developments without adequate archaeological assessment.

Arup’s cultural heritage team has undertaken cultural heritage assessment through involvement with large infrastructure projects such as HS1, Crossrail, and Thames Tideway Tunnel, where the pre-commencement archaeology conditions were secured through Parliamentary Bill and Development Consent Orders. However, much of the team’s other project work has been smaller scale infrastructure and other developments delivered under Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) permission. Our work is closely related to risk management – managing risk to the client and to heritage assets, and liaising with statutory consultees to ensure agreement, and proportionate protection of the historic environment.

Archaeological assessment informs the pre-commencement conditions, and reduces risk of destroying heritage – or the client overspending their budget – requiring an understanding of the site’s likely archaeological potential. The NPPF mandates an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process. Through this, we will provide a baseline on the likely significance of known and unknown heritage assets, developed through an understanding of Historic Environment Record (HER), non-intrusive surveys such as aerial photographs, LiDAR, geophysics and fieldwalking and, where appropriate, intrusive trench evaluation. This will be assessed against the construction impacts and effects. The amount of baseline detail is needed to ensure a robust understanding of significance and impact, so that unknown archaeology is identified prior to submission of the planning application as far as possible, to offset risk.

Fig. 1. Roman-period wall and earthwork bank construction deposits in the vicus of Benwell Roman fort or on the edge of the boundary of the fort, recorded during an evaluation prior to planning permission for a local extension. Photo: © Jon Welsh.

Risk for clients is balanced by helping them to determine if they should spend money up-front to robustly assess a site, including trench evaluation, with no guarantee of planning permission. Some clients prefer to wait until they have secured planning permission before committing extensive budget to archaeology (i.e. intrusive trial trenching): at that stage a pre-commencement condition may have greater ambiguity regarding how archaeology should be dealt with. The latter approach relies on ensuring that pre-commencement conditions are proportionate to the proposed development and the site’s heritage potential.

Two approaches are detailed here from recent Arup projects, which look at different ways in which baseline and impact information is used for defining the content of pre-commencement conditions.

An exemplar process is the recent Astra Zeneca site works, undertaken by Cambridge Archaeology Unit and managed by Arup. The outline planning application undertaken for Cambridge Biomedical Campus (CBC) construction projects (undertaken by others): a high potential of archaeology was identified through desk-based assessment (evaluating all known information about the area, primarily from the Historic Environment Record), supported by geophysical survey, aerial photographs and trial trench evaluation. This baseline provided a reasonably well-understood basis on which to trigger the requirement for a pre-commencement condition, to be factored in at later detailed design stage. For the Astra Zeneca site within the CBC development, the condition required archaeological works, namely area excavation, carried out over an eight-month period prior to construction. They identified and recorded multi-period archaeology dating from the Early Neolithic through to the early medieval period, including a significant pattern of Roman settlement.

At a site at London, desk-based assessment identified a low potential for archaeology on site, but with more significant remains nearby. This informed the outline planning application, and a pre-commencement archaeological condition was still applied for each plot as it was brought forward for development, including watching briefs (where archaeologists wait on site in case anything is found during construction). An oversight led to the violation of the pre-commencement condition – construction started early – and in discussion with the archaeological advisor to the Local Planning Authority (LPA), the developers were penalised by the construction of trial trenches. Although only limited archaeology was located, the trenches provided the first Roman evidence on the site.

We know that 25 years post PPG16, the process of managing archaeological risk is well understood in terms of content and purpose among planner and developers in most spheres. We do not want to return to pre-1991 situations. Under these conditions, archaeology declared following commencement of construction meant additional costs and delays to construction, so instead heritage was often destroyed. A solution to this concern is engaging robustly with LPA heritage advisors, through EIAs, heritage assessments, and other heritage planning documents, ensuring that under the process of proportionality, archaeology pre-commencement conditions are not seen as ‘excessive’ and more likely to be removed from the planning process, but as significant features of best practice planning.

However it may be time to start looking at what defines appropriate pre-commencement conditions? Does what we have currently work, or does it need to adapt to local situations, and are our LPAs appropriately resourced to tackle these situations? Given the ambiguity of the Bill regarding pre-commencement conditions and its implications, setting out the heritage industry’s concerns in a petition would be a valid approach.

An international perspective from the Middle East and North Africa

Emma Cunliffe, EAMENA

The archaeological heritage of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is of immense national significance, locally and to the world. The Romans built there, but before them civilisations like the Assyrians, Babylonians, Sumerians and countless others rose, flourished, and fell. The first cities, writing, law codes, and even the earliest known musical notation were all found there. Most of these countries lack a comprehensive Sites and Monuments Record, something we take for granted in the UK, although there is an online database available for Jordan (http://megajordan.org).

The Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA) Project, at Oxford and Leicester Universities (and Durham, coming soon!), works to record unknown archaeology and the threats to it across the MENA region (see ARA News 34, pp44–5. We’re primarily using satellite images and aerial photographs to map the sites and the problems, and carrying out trend analysis to determine the major threats.

When you think of the MENA region, most people think of the devastating conflicts tearing the region apart, but our work is highlighting the importance of overlooked causes of destruction – such as development. Housing pressures in the region are the same as pressures anywhere: people need a place to live, and that means roads, gas, electricity, sewage, and all the other infrastructure that goes with that. The MENA has nothing like PPG16, or EIAs, or any of the other host of legislative acronyms that dictate the management of archaeology during development. That’s not to say there aren’t dedicated heritage professionals managing the sites. In fact, the region has some of the most dedicated professionals you’ll ever meet, but there’s so much out there that they have their hands full keeping the developers off the edges of the known sites, never mind the ones not yet recorded.

Comparing 1960s CORONA satellite images to modern Google Earth imagery shows massive increasing development, which has devastated sites and archaeological features. But – I hear you say – PPG16 didn’t come in until 1991, even here, so surely it’s not a fair comparison. Ah, you were paying attention.

Recent development is possibly even more extensive, and changes in building methods mean that houses that once would barely have broken the surface now have cellars and floors underground, destroying the buried archaeological layers. Mind you, in some areas, archaeology is quite popular with developers – it’s a convenient source of pre-cut stone for your new house!

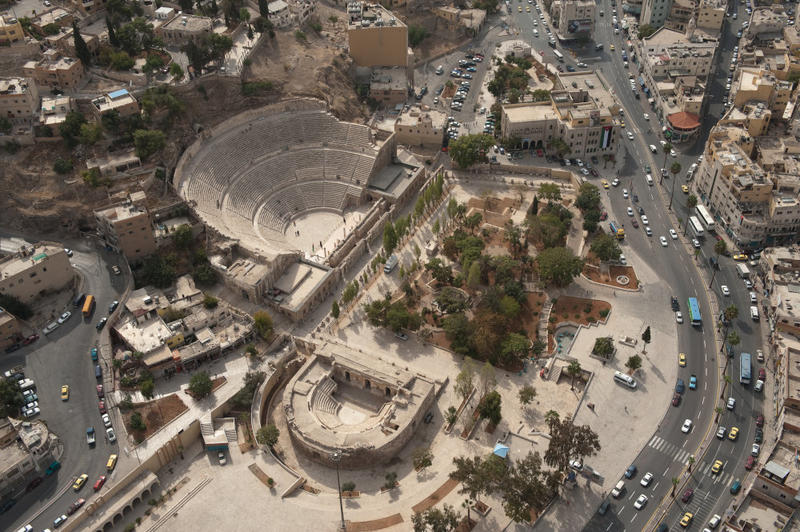

Fig. 2. Development around the forum and theatre in Amman, Jordan, 2009.

Fig. 3. Development around Roman baths, Damascus, Syria, 2003.

Photos: © David L Kennedy, Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East.

Fig. 4. Machaerus Roman fortress, Jordan, 2006.

Fig. 5. Machaerus Roman fortress – Camp P, Jordan, 2014.

Photo: © David L Kennedy, Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East. Photo: © Mat Dalton, Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East.

Kennedy and Bewley carried out aerial photography around Amman, Jordan, recording ‘small towns, villages, farmsteads, mansions, rural churches and shrines, burial places, industrial sites and the network of roads linking them. Due to modern development, such remains… have largely disappeared… In most cases they were recorded only superficially; sometimes not at all.‘6

That might sound depressing, but that’s where our work is vital. Without an understanding of the threats to sites, we cannot begin to devise protection strategies. We’re working with local heritage authorities across the region to map heritage in advance of major infrastructure projects, and providing tools for them to record and protect their heritage themselves. In Jordan, we identified 141 potential threatened sites in advance of a major ring-road project for the Department of Antiquities (DoA). Later this year we’re working in Iraq, partnering with the American University of Sulaimani and the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities, to showcase best-practice heritage protection projects and run training in heritage recording tools.

At the end of the day, heritage staff have limited resources, and construction is seen as key to economic development. For us, it’s a race against the clock to record what we can, and help our colleagues to target their limited resources to protect the most important sites.

I’ve spent my career recording the massive destruction occurring from development in the Middle East. Now I see UK agencies with a long history of supporting British archaeology, such as the Council for British Archaeology, openly voicing concerns regarding the proposals laid out in the new Bill: ‘These proposals seem to go against the wider commitments of the Government to sustainable development and historic environment protections.’ I have to agree with the CBA, that these proposals do not seem to support the protection of our past. We’ve a long way to go to get 100,000 signatures, but if that’s the only way to get the Government to take our concerns seriously, then as far as I’m concerned, we’d best get a move on!

And now it’s up to you. For more information, the Council for British Archaeology are co-ordinating7 raising these issues with the Government, and you can find the petition and response at: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/130783

Notes

3 Government response to petition, available https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/130783

4 Jonathan Lester works to promote archaeology to the public, and is an archaeology blogger: https://gingerarchaeology.wordpress.com/

5 ‘Lack of archaeologists “will bring UK to a halt” by Cahal Milmo, iNews 15 May 2016.

6 Kennedy, DL and Bewley, R (2010) Archives and Aerial Imagery in Jordan. Rescuing the Archaeology of Greater Amman from Rapid Urban Sprawl. In Cowley, D, Standring, RA & Abicht, MJ (eds) Landscapes through the Lens: Aerial Photographs and Historic Environment. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp193–206, p198.