Results from the EAMENA aerial photograph appeal: St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai (Egypt)

Posted 15/1/2018

Drs Letty ten Harkel, Michael Fradley and John Winterburn write

In May 2017, the EAMENA project launched an appeal for historical aerial photographs to aid the team in the identification of archaeological sites and possible factors threatening them. A subsequent post on the same appeal in the Royal Air Force Association magazine Air Mail led to a number of responses, including one from John Clubb, a former navigator in 683 Squadron RAF. This squadron performed a photo-survey role in the Middle East and North Africa during the early 1950s. John kindly allowed us to scan his personal photographs from his time in the squadron, which included two oblique views of St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai region of Egypt. These two images allow us to undertake a detailed assessment of landscape change around the site over the last half century.

St Catherine’s is an important site for Biblical scholars, and the prophet Mohammed is also said to have visited the monastery. It is situated in the Wadi ed Deir, on the eastern edge of Jebel Musa/Mount Sinai in Egypt. It is believed to be the Old Testament location where God appeared to Moses in the Burning Bush, and where Moses received the Ten Commandments. The monastery, also known as a castrum-laura because of its dual functionality as fortress and monastery, is commonly attributed to the 6th-century Emperor Justinian, making it the oldest continuously occupied monastery in the world. However, the history of monasticism in the St Catherine area can be traced back further still to the widespread arrival of anchorites in south Sinai during the 3rd century AD. Some of the monastic buildings – most notably the chapel constructed on the site of the Burning Bush – are attributed to the reign of Constantine in the 4th century AD (Mount Sinai Monastery website).

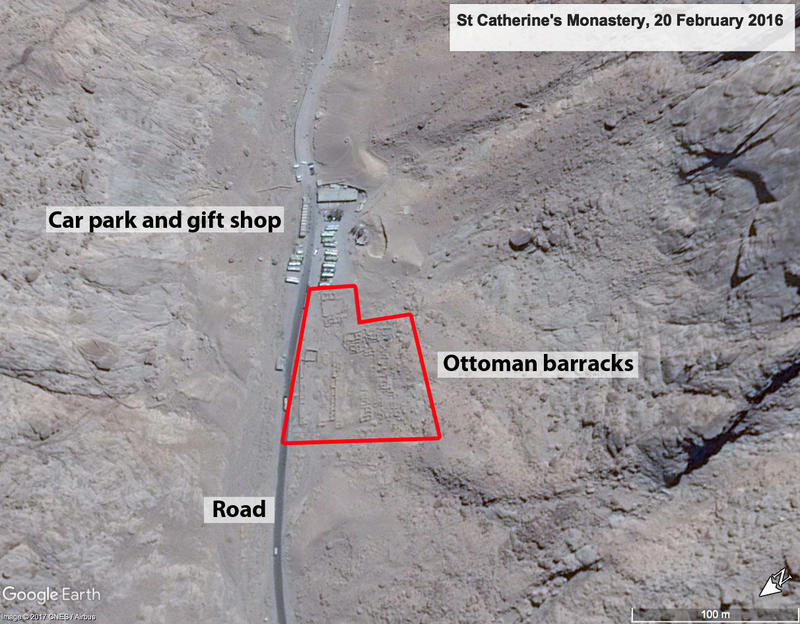

The example of St Catherine’s Monastery clearly shows how valuable historical photographs are for our understanding of the development of archaeological sites (Saint Catherine Monastery, Egypt). Until we obtained the 1951 oblique aerial imagery, our assessment of the site predominantly relied on Google Earth imagery, which is currently available for the period 2005–2016. As Figures 1 and 2 show, relatively little about the monastery had changed: some vegetation was removed or grew taller, but the buildings and outbuildings and traces of earlier structures to the south-east of the monastery remained the same. These earlier structures are likely to be the recently excavated quarters for soldiers and their families, involved in the construction and protection of the monastery during the sixth century AD (Mount Sinai Monastery website).

Unsurprisingly, the 1951 imagery shows that much more substantial change occurred in the c.50 years between 1951 and 2005 (Figure 3). Although the buildings within the monastery compound itself did not change much at all (some, after all, had been standing since the 1st millennium), the surrounding area underwent significant alterations. More buildings were constructed in the monastery grounds to the north-west of the main compound, and some of the trees grew substantially. The enclosure to the east of the main compound, visible on the 2005 imagery, seems to have been constructed or expanded during this period as well. Finally, on the 1951 imagery there is as of yet no clear sign of the 6th-century quarters for the soldiers who built the monastery buildings, bearing witness to the fact that archaeological excavation can alter the landscape as well.

Most noticeably, a comparison of the available imagery reveals that the access roads to the monastery were formalised and tarmacked during this period. The effects of increased ease of access to this once-remote site are immediately apparent from the vehicles parked in the car park to the north of the main compound. Attempts are made to keep visitors’ numbers restricted: the site ‘does not constitute an organized tourist site’ and visitors are treated as pilgrims (Mount Sinai Monastery website). Since the 19th century, however, travellers to St Catherine’s Monastery have increasingly included people who came out of curiosity and/or scholarly interest, rather than as pilgrims. In fact,

…it was Thomas Cook who made the Holy Land and Sinai popular with the affluent middle classes of Britain and other countries … the “Cookii”, as the Bedouin nicknamed them, opted for camping outside the Monastery walls and enjoyed familiar delicacies like Yorkshire bacon and potted salmon (Manginis 2016: 181; Princeton University Library 1960).

Nevertheless, the monastery remained difficult to access: as late as 1962 it was commented upon that ‘cars may get stuck in the sand, and have to be dug out again’ (Bassili 1962: 113).

Additional interesting information can be gleaned from a second oblique photograph, also dated to 1951, but taken from a different angle (Figure 4). This photograph, taken from the north-west, shows St Catherine’s Monastery itself in the background. In the foreground, the ruined remains of structures are clearly visible. One group is arranged in rectangular fashion around a central open area straddling the road – then still a dirt road – to the monastery. A second group, also arranged in rectangular fashion, sits alongside the road closer to the monastery whilst a third, more ill-defined, group sits back further from the road to the south. By 2005, but more clearly visible on the 2016 imagery, the tarmacked road runs right past it, having slightly changed course, and a car park (seemingly for tour buses) and gift shop is constructed immediately to its east (Figure 5). It is also clear that, at this stage, the structures had deteriorated significantly in comparison to 1951, suggesting that they were fairly recent when the 1951 photograph was taken.

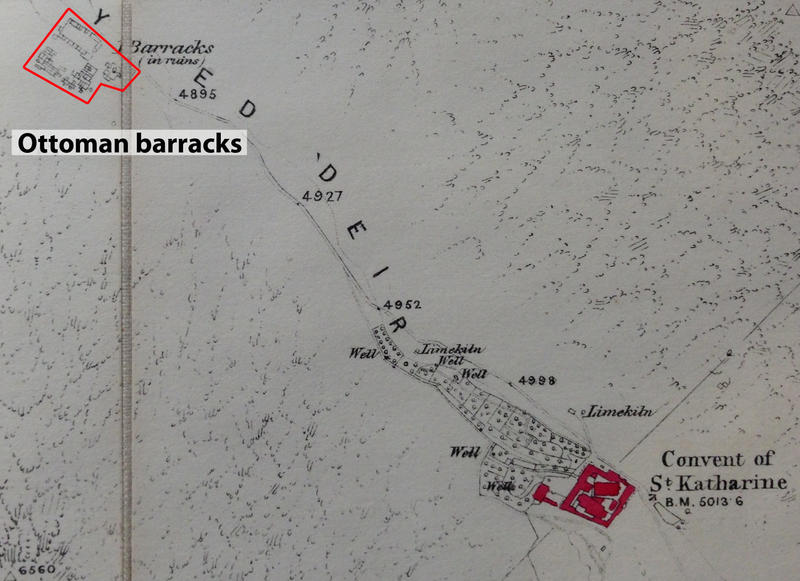

The 1869 Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai holds clues to the identification of these structures (Figure 6). The same structures are visible on one of their maps (scale 6 inches to a mile), situated between the monastery and a camp of the Royal Engineers dated to 1868 (see McDonald 1869). They were labelled as ‘barracks’, and already in 1869, they were described as being ‘in ruins’. Although there is no specific indication of the date of these barracks on the map itself, the accompanying descriptive text includes a passage on ‘the more modern works in the neighbourhood of Jebel Músá’, which focuses on the roads and summer palace of ‘Abbás Pasha, ruler of Egypt from 1848–1854 (Wilson and Palmer 1869: 209). The palace and some of the roads were never finished but Wilson and Palmer (1869: 209) state that ‘in Wády ed Deir are the ruins of the barracks, magazines, and mosques used by the soldiers of ‘Abbás Pasha whilst employed on the roads and palace’.

The tarmacking of the road to St Catherine’s Monastery on a slightly different alignment, avoiding the 19th-century barrack structures rather than running through the middle of it, is a positive development, having decreased the risk of further erosion of the site. At the same time, however, its close proximity may pose a risk to the longer-term survival of the site. Frequent traffic may cause pressure and compaction of underlying deposits, and future road repair may involve topsoil stripping, bulldozing, or the leaching of chemicals that may be damaging to fragile archaeological deposits.

The Ottoman barracks and the Royal Engineers Camp (McDonald 1869) are both evidence of the multi-layered landscape combining pilgrimage, militarisation and imperial ambitions that began with the Emperor Justinian. These sites form the wider landscape of Wadi ed Deir, but are themselves threatened by the expansion of tourism and the construction of access roads. This is of concern because the archaeology of more recent time periods remains relatively undervalued in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean, at least in comparison to Biblical, Classical, and prehistoric archaeology (Baram 2007: 11). In order to do justice to the long-term history of the Wadi ed Deir, the EAMENA team is now undertaking a more in-depth study of the landscape around St Catherine’s Monastery which will also take in account additional imagery from the APAAME archive.

Bibliography

Baram, U. 2007. Archaeological surveys, excavations, and landscapes of the Ottoman Imperial Realm: an agenda for the archaeology of Modernity for the Middle East. In S. Gelichi and M. Librenti (eds), Constructing Post-Medieval Archaeology in Italy: a new agenda. Prceedings of the International Conference (Venice, 24th and 25th November 2006), 11–18. Borgo San Lorenzo: All’insegna del giglio.

Bassili, W.F. 1962. Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: a practical guide for travellers. Fourth Edition. Cairo: Costa Tsoumas Printing House.

Manginis, G. 2016. Mount Sinai: a history of travellers and pilgrims. London: Haus Publishing Ltd.

McDonald, J. 1869. Royal Engineer’s (sic) camp in Wady ed Deir, and Jebel Sona, 1869: http://bit.ly/Sinai_1869. Accessed 23 November 2017.

Mount Sinai Monastery website: http://www.sinaimonastery.com/index.php/en. Accessed 17 November 2017.

Princeton University Library 1960. Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St Catherine: an exhibition based on the expedition sponsored by the University of Michigan, Princeton University, and the University of Alexandria. Princeton: Princeton University Library.

Wilson, C.W. and Palmer, H.S. 1869. Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai Part 1: account of the survey with illustrations. Southampton: Ordnance Survey.

Figure 1 Google Earth imagery of St Catherine’s Monastery, 11 June 2005

Figure 2 Google Earth imagery of St Catherine’s Monastery, 20 February 2016

Figure 3 Oblique aerial photograph of St Catherine’s Monastery looking north, taken by John Clubb (683 Squadron RAF) in 1951

Figure 4 Oblique aerial photograph of St Catherine’s Monastery and Ottoman barracks in the foreground, looking south-west, taken by John Clubb (683 Squadron RAF) in 1951

Figure 5 Google Earth imagery of Ottoman barracks near St Catherine’s Monastery, 20 February 2016

Figure 6 1869 Ordnance Survey map of St Catherine area showing Ottoman barracks ‘in ruins’; original map in Bodleian Libraries, Oxford