Balancing Conservation and Tourism in St. Catherine’s Protectorate, South Sinai: Reflections on a 2-week placement with EAMENA

In September 2021, I spent 2 weeks on a student placement for EAMENA. I worked on a project looking into the ‘traditional lifestyles’ of South Sinai, under the supervision of Dr Letty ten Harkel. Using Google Earth’s satellite imagery, I looked for archaeological sites tied to the lives of people in South Sinai and learned how to prepare a bulk upload sheet with the sites I found for logging in the EAMENA Database. At first, it was difficult to tell the difference between trees, rocks, and archaeological sites, but it was exciting whenever I discovered something archaeological.

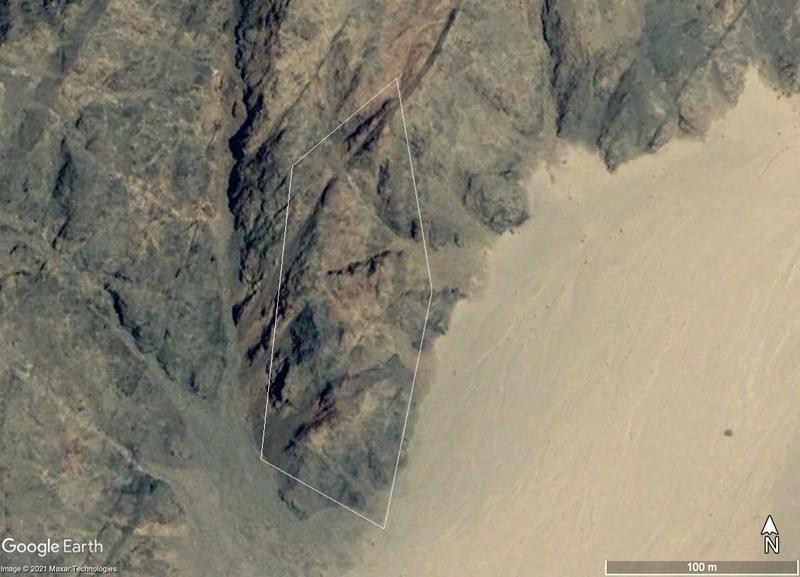

Figure 1: Two sets of enclosures separated by a wadi |

Figure 2: A path |

Although I marked and recorded some sites which I couldn’t identify (and which might well be natural), the archaeological sites I recorded were mostly enclosures, which look like dark wiggly circles (fig. 1); paths, zigzag white lines in the mountains (fig. 2); and funerary cairns, which look like black bullseyes (fig. 3).

Figure 3: A funerary cairn, threatened by the road which appears next to it

What I found the most interesting about this experience was learning about the interactions and tensions between conservation and tourism/industry. The area I studied is part of the St Catherine's Protectorate. This area is officially protected under Egyptian law, both for its ecological diversity and its wealth of cultural heritage sites. However, in practice the protection isn’t always well-enforced, and the area is under threat. One major threat is an increase in tourism, including eco-tourism, historical tourism, and visitors to towns inside and outside the protectorate. Increased tourism also leads to increased urban development.

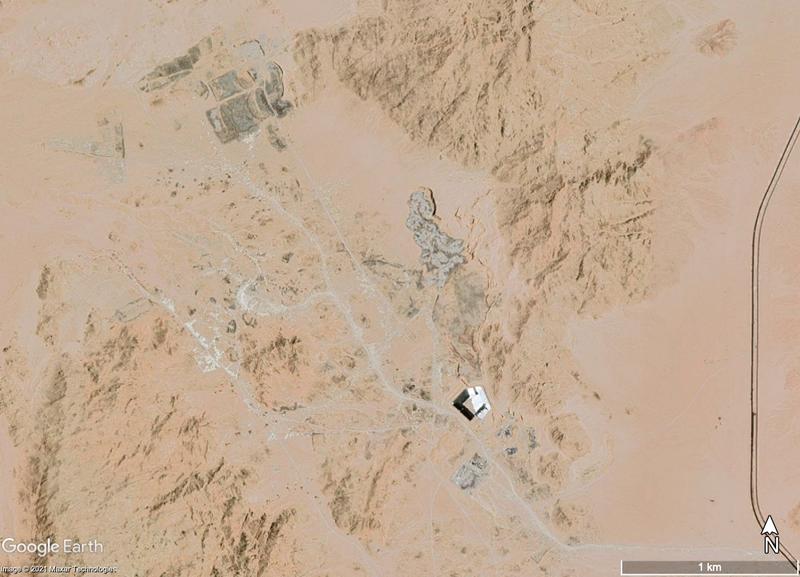

Figure 4: Satellite imagery from February 2007, where the Sharm El Sheikh rubbish ground build up will later appear |

Figure 5: The rubbish grounds for Sharm El Sheikh, built on the boundary of the St Catherine Protectorate, May 2021 |

I found evidence of this risk in my studies, in the shape of the Sharm El Sheikh rubbish dump. Sharm El Sheikh is a growing city and a major tourist hub on the gulf of Aqaba. The city itself is outside the protectorate; unfortunately, its rubbish dump is located on the boundary of the protectorate. Both the rubbish dump and the associated building projects have grown considerably in successive satellite imagery, which poses a threat to the archaeology and the ecosystem of the region. In 2007 (fig. 4), little is visible, but by 2021 (fig. 5) the satellite imagery shows considerable construction around the rubbish dump. For example, a road connected to the Sharm El Sheikh infrastructure shows up in later satellite imagery next to a funerary cairn (fig. 3). The traffic from the road may threaten the structure or continued existence of the cairn. From a purely archaeological perspective, tourism and development seem like bad things which threaten cultural heritage. Even so, tourism and development can be sources for social good. I was lucky enough to be able to attend a research presentation while I was on my placement with EAMENA, presented by my supervisor and two of her colleagues. Dr Ahmed Shams, director of the Sinai Peninsula Research (SPR) project and an external consultant to the EAMENA project, spoke persuasively about another, more practical, way of looking at conservation. He pointed out that the most successful conservation projects have been those which were locally managed.

Additionally, he discussed the role of the government and how their focus is often justifiably not on conservation. For example, the Egyptian government has a strong interest in maintaining and encouraging tourism, because of the revenue it brings in. They will have no interest in a plan which seeks to reduce tourism, even if that would help conserve the protectorate. Therefore, Dr Shams argued, archaeologists and conservationists should seek to work with local representatives to balance tourism with conservation so that both benefit (after all, the money from tourism can be important in funding conservation work).

Figure 6: A traditional but recent field, which only appears after 2013

Continuing practice also needs to be considered in conservation. In my remote survey, I came across an agricultural field which appeared only in more recent satellite images (fig. 6). If it had appeared in the earliest satellite imagery, I would have labeled it as archaeological; within my limited understanding, it looks like a continuation of traditional practices. Technically, new agriculture is labeled a threat to archaeology, since the activity can upset archaeological sites. However, sites like this one can also be important parts of conservation as they continue the very practices which archaeology is seeking to document and preserve.

It sometimes seems that for archaeology, it would be easiest if heritage sites froze just the way they are, with no additional threats or change. Of course, this is unrealistic; people continue living and changing and causing the very effects on the landscape which archaeology studies. My work on this project has demonstrated for me the excitement in archaeological research, but it has also made me consider the balance between conservation and other economic concerns.

Additional Reading

Amara, D. (2017). ‘Responsible marketing for tourism destinations: Saint Catherine Protectorate, South Sinai, Egypt’, Journal of Business and Retail Management Research.

Gilbert, H. (2014). ‘The Monastery Is Our History’: Development, Change and Continuity for St Katherine’s Bedu’, The Fortnightly Review.

Shams, A., and Ten Harkel, L. (2019). ‘The SinaiArchaeoWater Project (SAW)’, EAMENA blog.

Ten Harkel, L., Fradley, M. and Winterburn, J. (2018) ‘Results from the EAMENA aerial photograph appeal: St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai (Egypt)’, EAMENA blog.