Endangered Archaeology as captured with the Aerial Archaeology in Jordan Project: September 2016 Season

Rebecca Banks tells us about the work of the Aerial Archaeology in Jordan project in 2016

In 2016, Dr Robert Bewley, Prof. David Kennedy, Dr Andrea Zerbini, and I had the pleasure of conducting several reconnaissance flights with the Aerial Archaeology in Jordan project (see our affiliate project page). These flights not only remind us of the significance of the archaeology in the region, but also highlight the causes and effects of threats to those archaeological sites. Here are some examples looking back at the results of the 2016 flights, with some comparisons to images from previous years. You can see the entirety of the photographic material through the APAAME website.

Excavation: Tell el-Hammam

The site of Tell el-Hammam is a large, elongated tell located in the eastern extent of the Ghawr al-Kafrayn, which joins the Jordan Valley to the west. Comparing recent photography with the CORONA satellite imagery of 1967 shows how drastically the surrounding landscape has changed: it has become surrounded by the expansion of agricultural production in the Jordan Valley. Also evident is the population expansion with increased housing density, and road routes that proceed from the plain and up the slope of the tell are visible. The most recent disruption to the tell, however, is one of archaeological enquiry: the Tell el-Hammam Excavation Project (College of Archaeology, Trinity Southwest University, and Jordan Department of Antiquities). The 2016 photographs show not only the progress of the excavations over the site, but also the secondary changes occurring around the excavation trenches. The excavations have revealed evidence for Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Early, Intermediate, Middle and Late Bronze Ages, Iron Age 2, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic occupations, but the bulk of the occupation material belongs to the Early Bronze Age (3600–2500 BCE), Intermediate Bronze Age (2500–1950 BCE), and Middle Bronze Age (after 1950 BCE). The 2016 photography shows the progress of the excavations over the site, but also the secondary changes occurring around those excavation trenches.

Landscape change: Development

A small pocket of trees north of the site of Libb had been photographed in the past by AAJ, most recently last year, looking for a possible Roman road. This year, we were surprised by drastic changes in the landscape caused by the excavation and construction associated with a development project. This example demonstrates the speed and the extent of landscape change that can occur within a short period of time.

APAAME_20161002_AZ-0132

Landscape change: Quarrying

This large limestone quarry is located in the vicinity of the site of Samad (middle and right of picture), a well-preserved Ottoman village built on top of an earlier Byzantine and Umayyad settlement. Cairns, field systems, and tombs in the hinterland of Samad are directly affected by the expansion of this quarry and its associated infrastructure.

Road development: Limes Arabicus Survey Site 532, Kerak Resources Project Site 575

This extensive site east of the Kerak Plateau has been damaged from the upgrade of a road. The site has already been investigated by two archaeological surveys; it is multi-period and may have been the location of a caravanserai, a safe point to stop on a route along the Wadi el-Yabis, according to the Limes Arabicus Survey (Parker 2006: 107). The forthcoming publication of the Kerak Resources Project Survey may offer us more insight. Unfortunately, the levelling and widening of the road has partially or completely destroyed some features, while others not in the direct path of the road seem to have been inexplicably targeted by bulldozer activity. The upgrade of the road may also introduce increased activity in the area, resulting in potentially negative impacts on the site.

APAAME_20160919_RHB-0174

Mandate period stone robbing

Several fortification sites in Jordan were used as quarries to build Mandate period forts. This is the site of Quweira: the reservoir (centre) is a repurposed ancient reservoir, the low mound to its left is an ancient Roman fort, and the partially roofed structure further to the left is the later Mandate-era police fort. The current appearance of the site, however, is misleading. The superstructure of the ancient fort is clearly not visible, implying that it has been largely destroyed; however, sondages undertaken at the site in 1989 by David Graf have demonstrated that sections of the structure are still well-preserved underneath a large deposit of sand (see Kennedy 2004: fig. 19.8). This is a good example of combining evidence from fieldwork with aerial investigations – a good practice whenever possible.

APAAME_20160919_RHB-0282

The fort at the site of Bayir Wells, an isolated ancient watering stop in the south of Jordan, was successfully photographed in 2016 after previous attempts to capture it failed. We can see why it proved elusive from the photograph: it has been drastically reduced by stone robbing for the nearby Mandate-period police fort (built 1932, not pictured), as well as for the stone cairns or enclosures that mark the sites of Bedouin burials at the site (not pictures; see Field 1960: 100). The fort was long thought to be early Islamic, but ground surveys at the site give evidence for a predominantly Nabataean occupation, with some Roman and possible late Roman (King et al. 1983 ADAJ: 398–399).

APAAME_20160919_RHB-0174

Cemeteries

What we thought initially was a new wave of looting at the Nabataean/Roman settlement and fort site of Qirana is, in fact, the extension of an existing modern cemetery on the site. Archaeological sites and tells are commonly used as the location of later cemeteries or burials both in ancient and modern times. The new activity at Qirana, probably conducted by machinery as suggested by the uniformity and size of the excavations, has disturbed a section of the site alongside the modern road on the southwest edge of the settlement. This type of excavation activity results in displacement of archaeological material, and stone is often reused from the surrounding structures of the site to mark the extent of the new graves when filled.

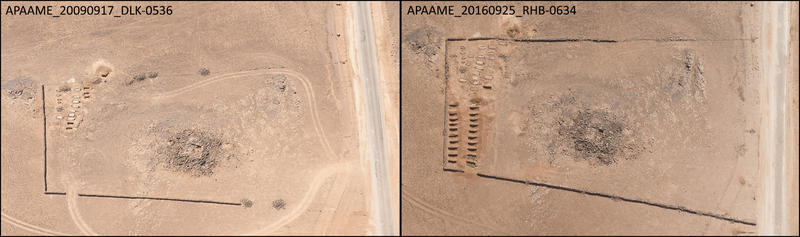

Similar activity was also photographed in 2016 at the site of Qasr Huweinit, a roadside tower. A section of the demarcated area of the site was dug to expand an existing cemetery between 1998 and 2009, and this year’s flight records a further expansion.

Inexplicable bulldozing

APAAME_20160922_RHB-0196

The basalt desert is rife with bulldozing. In the following examples the archaeological sites pictured, known as ‘pendants’, were not the target, but nonetheless affected. The reasons for bulldozing in the desert are many and varied, e.g. clearance for paths or fields, collecting stone, or demarcating land parcels. Unfortunately, no heed seems to be taken of the low, stone-built structures that profusely populate the surface of the desert.

Bulldozing along the edge of this pendant structure is the result of increased activity in the vicinity of the site caused by the building of the new Azraq by-pass.

APAAME_20160922_RHB-0555

The importance of a water source: Biyar el Ghusein

The site of Biyar el Ghusein was photographed for the first time in 2016. This remote water source in the badia is clearly still used to this day, with current, lined wells that have been dug into the wadi floor still showing evidence of water at their bottom, and earlier, collapsed wells evident around them. The site is surrounded by enclosures, cairns, pendants, and modern and ancient tracks, demonstrating a long period of human occupation.

Site restoration, conservation and maintenance: Qasr el-Hallabat

The central fort complex at the site of Qasr el-Hallabat has undergone extensive site restoration and conservation efforts. In these photographs you can see that the ruined main fort and associated structures, including a mosque, have not only been excavated and cleared of fallen debris, but large sections have also been consolidated and/or rebuilt. The structure is the result of several building phases on the location, from a fortlet of 17.5 m square, to the Umayyad residence complex we see restored today. The site of Hallabat has produced evidence from the Nabataean to Early Islamic periods, but the exact dating for the initial fort at the site is unclear.

The restoration efforts have greatly clarified the structure for visitors, and a visitor centre and gallery (located out of picture on the edge of the archaeological park) have also been added to the site. The restoration has stabilised the structure to prevent further collapse, but has also rebuilt sections, which today make the site a pastiche of ancient structure and modern archaeological interpretation and rebuilding.

APAAME_20160927_REB-0022

Not visible on the satellite imagery: Caves at Sirfa

The modern village of Sirfa is built on and around an ancient site, but the most visible elements of that in the photograph are the early 20th century buildings with collapsed ceilings. These villages have reused the stone of the ancient structures on which they stand. Our first reports of the site before settlement are from the 19th century. This aerial image also captures a number of caves on the southern edge of the site, where the Archaeological Survey of the Kerak Plateau (Site 52) records the highest concentration of sherds, though does not mention the caves. The aerial investigation better represents to us the possible full extent and use of the ancient and modern site.

Domestic development: Khirbet al-Mahramah

The site of Khirbet al-Mahramah has been increasingly encroached upon by the expansion of the nearby village of Mazar al-Shamali. The tell site is an ancient settlement with surface pottery dated from the early Roman to Mamluk periods. In the early Roman period, it is likely to have been a site of some importance, as Latin inscriptions attesting to the presence of Roman army veterans suggest. Before AAJ surveyed the site in 2011, Khirbet al-Mahramah had already been damaged by bulldozing activity aimed at the preparation of new olive orchards, as well as by the laying of a dirt road established ahead of the construction of several new houses. The site was surveyed again by the French survey mission ‘Mission Haute Jordanie’ in May 2016, who alerted us to the fact that further damage had occurred at the site. Air reconnaissance in September 2016 showed further evidence of bulldozing, new housing, and increased looting on the top of the tell.

APAAME_20161002_AZ-0126

Agriculture and burning: unnamed site (Jarash Ruin 31)

This site, probably an early Islamic settlement, was surveyed by the French ‘Mission Haute Jordanie’ in May 2016. The site, which is identifiable by the colour difference in the soil and low rubble, has been partly bulldozed to make space for modern olive groves. Burning, possibly by grass fire, also seems to have affected the site recently.

Overall, the 2016 season of flying was a massive success, but once again highlighted to us the urgency and importance of active aerial reconnaissance programmes for monitoring changes to the archaeological and heritage landscape of Jordan. If you have any information regarding sites that have previously been photographed by AAJ or would like to suggest a site that would benefit from monitoring by AAJ in the future, please contact us or APAAME.

Works cited:

Clark, V.A., Koucky, F. L., & Parker, S. T. 2006. Chapter 2. The Regional Survey. In: Parker, S. T. The Roman Frontier in Central Jordan: Final Report on the Limes Arabicus Project, 1980-1989. 2 vols. (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks).

Field, H. 1960. North Arabian Desert Archaeological Survey, 1925-50, (Cambridge MA, The Peabody Museum).

Kennedy, D. 2004. The Roman Army in Jordan. 2nd edition, (London, Council for British Research in the Levant/ The British Academy).

King, G., Lenzen, C.J. & Rollefson, G.O. 1983. Survey of Byzantine and Islamic Sites in Jordan. Second Season Report, 1981. ADAJ 27: 385–436.

Miller, J. M. & Pinkerton, J. M. 1991. Archaeological survey of the Kerak Plateau conducted during 1978-1982 under the direction of J. Maxwell Miller and Jack M. Pinkerton (Atlanta, Ga., Scholars Press).