Lebanon’s Heritage at Risk: Part 3

Posted 8/5/2017

Drs Jennie Bradbury, Pascal Flohr, and Letty ten Harkel conclude our examination of Lebanon’s Heritage At Risk

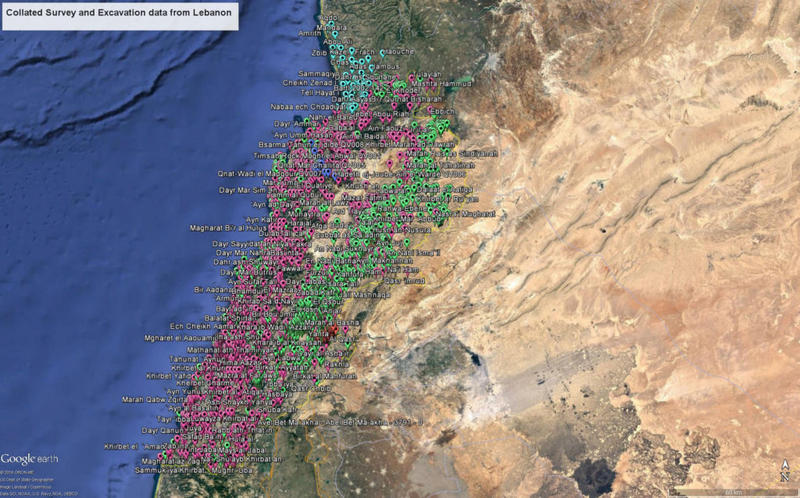

Since the beginning of 2017, one of the tasks the EAMENA team have been busy working on is collating and digitising existing data from surveys and excavations in Lebanon. These are published in a variety of places and ways, ranging from, for example, synthetic overview reports, to institute newsletters and archaeological journals. Bringing together all of these data requires a substantial amount of time and effort. It is ultimately, however, very worthwhile. By digitising existing data we can build up a picture of what work has been carried out and where. This allows us to target our investigations to focus on areas that have not been so intensively surveyed or investigated and thus would potentially benefit from further research via remote sensing. Using information from sites that have already been identified is also an important step in helping to validate our findings. For example, knowing what already-documented sites look like on satellite imagery can help us to identify similar unrecorded features elsewhere in the landscape. Bringing together data on excavated and surveyed sites can also help us to understand and explore landscape changes and disturbances that have affected these sites since they were initially identified and investigated by archaeologists.

Our work starts online, in the library, and by working with local contacts and archaeologists who have active projects in Lebanon. A simple, initial task was to go through existing journals, such as the Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises, to identify where surveys and excavations had been carried out. All projects working in Lebanon are required to publish their work in this journal and so it is a good starting point to identify past and current investigations. Another useful source is the (partially) open-access journal Archaeology and History in Lebanon, published by the London-based Lebanese British Friends of the National Museum (LBFNM).

One of the aims of the EAMENA Project is to create networks and share knowledge, and it is in this inclusive spirit that we draw on existing data. The EAMENA database allows us to record full bibliographical details for existing survey and excavation reports and other digital resources that have been shared with us so that we can fully acknowledge the work carried out by other heritage professionals. In addition to collating material from different resources and conducting our own remote satellite surveys (Blog (3rd Jan 2017), however, there are a number of ways that EAMENA is able to contribute to and enhance these existing data.

One of the main ways in which we can enhance published data is by combining and collating the results of multiple investigations of the same site(s), especially where they have focused on different aspects of their history. This is particularly relevant for complex sites, such as the well-known ancient port city of Tyre, where a Byzantine church was discovered only in the 1990s (mentioned in Waliszewski 2006: 32). There are other, less high-profile examples as well, such as the village of Hannaouiye (Hanāwīya) on the Tyre-Qana road in the South Governate. Here, the extensive published bibliography by Lehmann (2002: 107.144) identified material of the prehistoric, Hellenistic, and Crusader periods. Having also incorporated information from Waliszewski’s 2006 introductory discussion of Byzantine churches in Lebanon, however, it has now become clear that this was also the location of a 6th-century AD church with mosaic flooring, the first ever to have been discovered in Lebanon (in 1861, by Ernest Renan; Waliszewski 2006: 30). The EAMENA database is set up so that additions and corrections to the data can be added continuously, to acknowledge the evolving nature of archaeological investigation.

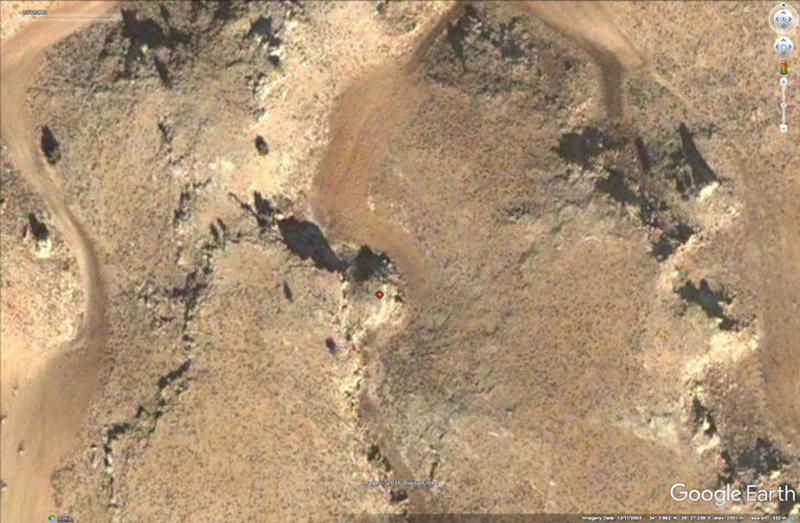

Collating data from published sources also comes with challenges. Publications of archaeological discoveries do not always include co-ordinates or detailed maps, especially when they pre-date the widespread use of GPS in archaeological prospecting. In some cases, published maps are only at country level or on a broad regional scale, which creates substantial (and variable) margins of error when geo-correcting them in a GIS to digitise site locations. In some cases, subsequent visual inspection of satellite imagery can help to locate the sites with more precision. For example, use of Google Earth imagery has helped the team to more accurately identify the location of probable Mamluk water mills and settlements in the Anti-Lebanon, based on a survey by Bonatz (2002). In other cases, this is unfortunately not possible. One problem is the various topographical and land-use factors that can obscure sites, some of which were highlighted in Part 1 of this blog series. Other problems include the fact that many sites known from excavations are simply not visible on the surface, and certain types of surface features – such as low-density pottery scatters – are also impossible to see on satellite imagery.

The archaeological sites on which existing surveys and excavations tend to focus are often multi-period settlements. Frequently, these are visible as large mounds (tells) which have been formed by thousands of years of human activity. These mounds are generally easy to spot in satellite imagery, but it can be difficult to distinguish natural hills from artificial mounds in more hilly regions. Combining remote sensing with data from existing publications helps in this, and in addition, the latter provide information that is not visible on the imagery, such as the period(s) of occupation.

Religious buildings, such as churches and mosques, are common throughout Lebanon. However, because these buildings are often still in use, whether or not in their original form, it can be difficult to tell how old a structure is from satellite imagery alone. Therefore, we use existing reports and photographs to gain this information. Ruins that are still standing, such as medieval-period villages or mills, are another common type of site visible on satellite images. Abandoned villages are relatively clear on the imagery, especially when roofs have started to fall in (if not, it can be difficult to know if the structure has indeed been abandoned). These are often found in relation to field systems. In most of the hilly and mountainous parts of Lebanon, as across much of the Mediterranean, terraced field systems are widespread and are likely to have been used for millennia. More recent (Ottoman) ruined villages and their field systems are very rarely mentioned in existing publications, as these tend to focus on older sites. These later periods, however, are also an important part of heritage, and indeed, as the recent survey by EAMENA’s Jennie Bradbury (Part 2) has shown, these villages can often date back to the Mamluk period.

In contrast, some site types are not visible on satellite or aerial images and can only be recognised on the ground. One example is field scatters of stone tools or pottery sherds, where more substantial remains, if there are any, remain hidden under the ground. A different colour might give away the presence of such a scatter on a satellite image, but this can also have many other causes. Archaeological remains in caves or rock shelters are another example of sites that, for obvious reasons, are not visible from above. It is therefore important to use existing data from ground surveys.

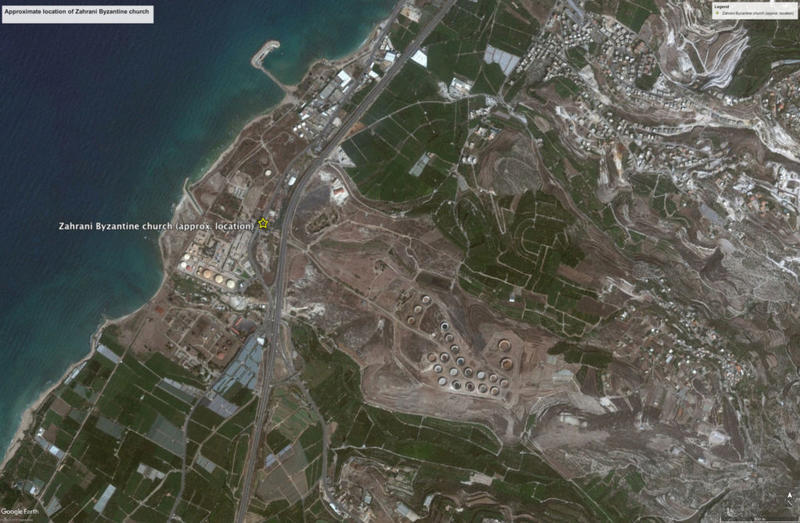

A final issue – and one that lies at the heart of the EAMENA Project – is the on-going destruction of sites. This is an area where the mapping of published sites in Google Earth can really make a contribution to our understanding of the threats to Lebanon’s rich archaeological heritage. In particular, it is incredibly useful to be able to combine field observations with satellite imagery analyses. Field reports can provide important time depth to the discussions. For example, although the project utilises satellite imagery and aerial photographs ranging in date from the early 20th century to today, much of the high-resolution imagery accessed and used by the project in Google Earth dates to the last decade or so. This means that published reports documenting sites prior to the early to mid 2000s can provide important details about disturbances and threats to the archaeology of this region prior to this time. Bartl (1998), for example, in her report on the Akkar Plain, mentions that settlement and agricultural activities had already destroyed a number of archaeological sites and were threatening others in the late 1990s. Another good example is the Byzantine church at ez Zahrani just south of Sidon (Waliszewski 1997: 291 pl. 1), located in an area of intensive industrial development (an exit port for crude oil) on the Lebanese coast. The site of the church – first published in the 1950s – is no longer visible on the available satellite imagery, but the exit port itself is.

Our research and data collation is still in progress and we have many more months of hard work ahead. Bringing together different datasets, however, will allow us to enhance records already existing within our database, add new sites, and ultimately, will allow us to achieve some of the key aims of the EAMENA Project.

References

Bartl, K. 1998. Archaeological Surface Investigations in the Plain of Akkar/Northern Lebanon. Preliminary Results. Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises 3: 169–179

Bonatz, D. 2002. Preliminary Remarks on an Archaeological Survey in the Anti-Lebanon, Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises 6: 283–307

Garrard, A. and Yazbeck, C. 2003. Qadisha valley prehistory project (Northern Lebanon) Summary of the first two seasons investigations. Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises 7: 7–14

Lehmann, G. 2002. Bibliographie der archäologischen Fundstellen und Surveys in Syrien und Libanon, Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH.

Waliszewski, T. 1997. Une église byzantine à Majdal Zoun (Liban-Sud), Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises 2: 290–306

Waliszewski, T. 2006. From the Roman Temple to the Byzantine Basilica at Chhîm (South Lebanon), Archaeology and History in the Lebanon 23: 30–41

Figure A. The collation of existing survey and excavation data is still a work in progress, but it is helping us to validate and target our investigations and build up a picture of what has been done where.

Figure B, C. Using Google Earth imagery to help locate Mamluk water mills (mathanet) and settlements in the Anti-Lebanon, based on Bonatz 2002.

Figure D. Tell al Ayyun in the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon. This artificial mound had already been documented previously, but is also clearly visible on Google Earth. The multi-period archaeological site is damaged by terracing, landscaping (the NE part appears dug away), ploughing, and modern construction.

Figure E. Tell-like natural hills in Anti-Lebanon (Image: CNES/Astrium 6/10/2014).

Figure F. Possible abandoned buildings or enclosures and terraces in Northern Lebanon. The nearby monastery of Qanubin had been documented previously, but often such Ottoman period structures tend to be neglected in surveys (Image: DigitalGlobe 22/3/2010).

Figure G. Nothing on the imagery suggests there is a Middle Palaeolithic artefact scatter associated with the limestone rock outcrop in the seasonal river bed (red mark), as found by Garrard et al. 2003. Prehistoric sites tend to get missed out when only using remote sensing (Image: DigitalGlobe 11/12/2003).

Figure H. The Byzantine church at ez Zahrani just south of Sidon. The site of the church – first published in the 1950s – is no longer visible on the available satellite imagery, but the exit port itself is.