Translating EAMENA’s platform into Arabic: challenges and solutions

H. Mahdy and A. Zerbini write about the challenges and solutions involved in translating EAMENA’s platform into Arabic

The EAMENA project documents endangered heritage in 20 countries in the Middle East and North Africa. In all but Iran, Arabic is the main language spoken in these countries. Therefore, in order to enhance the value of the EAMENA database as a heritage mapping and management tool for researchers and institutions based in the MENA region, the team has prioritised translating the platform into this language. Since April 2016, EAMENA has teamed up with Mr Hossam Mahdy, an architect who specialises in the translation of cultural heritage lexica from English to Arabic.

EAMENA’s platform is based on a customised version of Arches 3, the open-source heritage management platform developed by the Getty Conservation Institute and the World Monuments Fund (more about EAMENA’s customisation of Arches may be found here). The platform is made up of static text (on html templates) as well as dynamic text, the latter comprising controlled vocabularies (or glossaries) developed in-house by the EAMENA team and containing more than 2,200 individual concepts, each of which is accompanied by a definition.

Translating the EAMENA platform into Arabic has been a delicate task. Although Modern Standard Arabic (foṣḥa, often abbreviated as MSA) is used in formal and professional literature across the MENA region, each country has its own spoken dialect. Moreover, subtle differences in the choice of MSA synonyms are frequent in the MENA region: for example, the Arabic word for management is rendered in Tunisia by the MSA word tartib ترتيب, while in Egypt the MSA word idarah إدارة is preferred.

Furthermore, the very quick pace of technological advances is causing the adoption of different words in different countries for the same object or idea, such as the different functions and tools related to computers, the internet, smartphones, remote sensing, and satellite imagery, to mention but a few.

Another difference is caused by non-Arab cultural influences in different countries. For example, Amazigh culture and language in the Maghreb and French cultural and linguistic influences from colonial periods can be detected in the spoken Arabic of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. In Iraq, there are Persian, Kurdish, and Turkish borrowings, as well as English influences from the time of the British mandate, that occur in the country’s spoken dialect. A well-known example regards the names of months for the Gregorian calendar. In Iraq and the Levant, Assyrian names are given to the months (e.g. February is called Shbat شباط), while transliterations of French names are used in Algeria and Tunisia (e.g. February is called Fevrier فيفري ). In Egypt, Sudan, and the Arabian Peninsula, a distorted transliteration of English is used (e.g. February is called Febrayerفبراير ). In Morocco, the same transliteration is used (i.e. Febrayerفبراير ), but in this country the rendering of Gregorian month names is said to be a legacy of a custom of Moorish Andalusia rather than the product of more recent influences.

The approach that was adopted in translating the EAMENA platform prioritised the use of terms that are most likely to be understood by all throughout the MENA region. Wherever possible, an attempt was made to avoid words that may not be understood in some countries.

For the controlled vocabularies, the translation process included a further step. After an initial stage during which a first set of translations was prepared, experts from all MENA countries where EAMENA is working were approached to provide feedback on the choice of terms. They were asked to review the Arabic translation and highlight any words that might not be understood in their own countries. Thirty experts from twenty countries were approached, and twelve (from Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, UAE, and Yemen) responded positively and participated in the consultation process. Experts belonged to a range of disciplines that are relevant to the work of EAMENA, such as archaeology, conservation, anthropology, art history, and heritage management. Efforts were also made to have both male and female participants represented in the group of experts.

The experts were not asked to suggest their preferred choice of words, but rather to flag words that might be problematic in their countries, either because they are not understood or because their use conveys a meaning that differs from that intended by EAMENA. They were also asked to offer any comments or alternative translations.

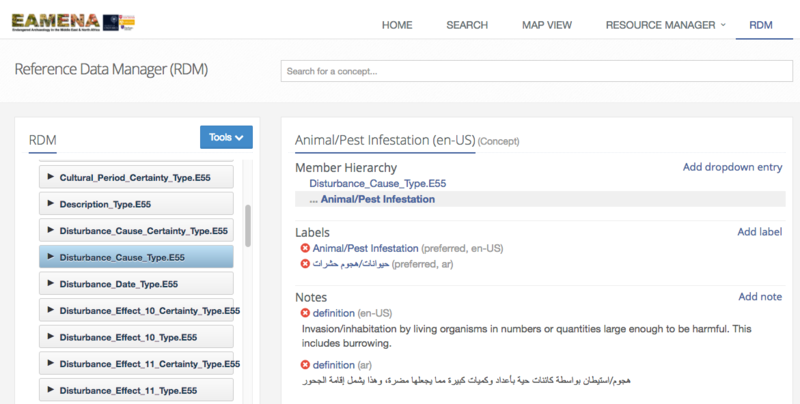

This feedback proved very informative and rewarding. In a couple of cases, linguistic mistakes made during the first translation phase were spotted. In other cases, much better alternatives were suggested. Most importantly, some words were flagged up as being unintelligible in a particular country, thus prompting the translator to offer an alternative choice of words. In this latter case, alternative translations (with a mention of their relevance for the countries to which they apply) have been maintained in the EAMENA platform, and are recorded as alternative concept labels and definitions in the platform’s Resource Data Manager (see figure below).

Screenshot of the ARCHES Reference Data Manager (RDM)

This process is still ongoing, particularly as EAMENA progresses, grows, and receives more feedback from different professionals in Arabic-speaking MENA countries. No doubt, more refinements will be made in the future.

By undertaking this Arabic translation, EAMENA aims to make its database more easily accessible to MENA researchers and practitioners in order to enhance its use for monitoring, management, and conservation. This translation will also contribute to a better understanding of and participation in the protection of archaeological sites by local communities in the MENA region.